By: Seth Culp-Ressler | Asst. Features Editor

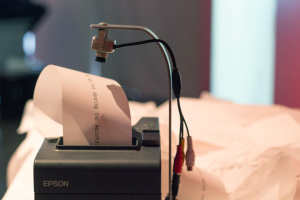

A small printer slowly but surely produced slips of sentences, a Wikileaks themed videogame stood ready for action and 15,000 vinyl records lay in wait for a spin on the turntable. Public Record, SPACE’s newest exhibition, opened its doors last Friday.

Coinciding with the quarterly Pittsburgh Gallery Crawl, Public Record’s debut marked yet another exhibition joining this year’s Pittsburgh Biennial, the city’s bi-annual collaborative art show.

The Biennial started at the Pittsburgh Center for the Arts in 1994. Through years of growth and expansion, the Pittsburgh Biennial is now the largest survey of regional contemporary art in the area, according to its website. This year eight institutions are participating in the Biennial — the Carnegie Museum of Art, the Pittsburgh Glass Center, Pittsburgh Filmmakers, the Pittsburgh Center for the Arts, the Mattress Factory, the Miller Gallery at CMU, SPACE and The Andy Warhol Museum.

Adam Welch, curator of the shows at both the Pittsburgh Center for the Arts and Pittsburgh Filmmakers, said that while the Biennial doesn’t technically have one set theme, as a whole it focuses on the importance of Pittsburgh’s local artists. Each individual venue was able to interpret what it thought the Biennial is all about, and because of that the Pittsburgh art’s wide variety of styles, mediums and individuals are all showcased together.

“The flux of artists that have come through [Pittsburgh]— working in a variety of different manners, styles and ways of thinking and creating — I think the Biennial mirrors that and tries to reflect on that,” Welch said.

One such local artist is Renee Piechocki, one half of the group “Two Girls Working,” who created the installation Taking Stock, one of nine within SPACE’s Public Record. The body of work that Piechocki and co-collaborator Tiffany Ludwig created for the show centers around one question they asked a group of men: “What do you do that makes you feel valuable?”

In Taking Stock, 10 men (well, technically nine men and one 10- year-old boy) were asked this question in an environment of their own choosing, with photographs and video documenting their answers.

“What you can see here in the gallery is the project question, photographs that have a very small text and then two videos — one two-hour long video that shows the full interviews edited with each person, and then an eight-minute video that’s actually going to be changing throughout the course of the show,” Piechocki said.

Piechocki went on to explain that since Taking Stock is an ever-evolving project, the shorter video will be continually added to as more interviews are completed, creating a dynamic aspect for the installation.

Public Record’s nine artists cover a range of artistic mediums, ranging from Piechocki’s Taking Stock to Paolo Pedercini’s Leaky World, a playable interpretation of Wikileaks founder Julian Assange’s essay “Conspiracy as Governance”. Aspirations, an audio-visual project by local Pulitzer-Prize winning photographer Martha Rial, explores the dreams of eight young adults with Aspergers Syndrome. Well Played: Paul’s Vinyl Records, which while still part of the show is actually located at 707 Penn Gallery, is an interactive display of artist Paul Rosenblatt’s 15,000 record collection, where music selections chosen by attendants are placed on a wall, forming a visual catalog of the gallery-goer’s tastes.

What the pieces all have in common, as gallery curator Murray Horne wrote in his foreword for the show, is their ability to “portray and pull aside the veils that hide.”

“Works at SPACE and 707 Penn Gallery demonstrates how, in the age of the internet and its attendant technologies, privacy and secrecy are in increasingly short supply,” Horne said. “With or without our consent, governments are exposed and personal intimacies revealed, instantly entering the public record with the tap of the keyboard.”

Piechocki was “honored” to be in Horne’s larger selection of the Biennial.

“I really like the theme that he’s created here about looking at how different content is displayed in the public realm … or not necessarily public, but shared with the public, I guess,” Piechocki said. “So every single one of these artists has a kind of public or interactive component, and I like that as a connecting thread.”

That idea of a connecting thread can be found not just in the collection at SPACE, but throughout the larger Biennial as a whole. As Welch explained, no one aspect of the event stands out — what is of note is the entire collection of participating artists and venues.

“I think one of the most phenomenal things that is being put across is that all these institutions are working together, and independently to their own missions and their own guidance, to really focus on some phenomenal work that is being produced in the area, and it’s on par with any national work or international work,” he said.