Kellen Stepler | editor-in-chief

10/08/20

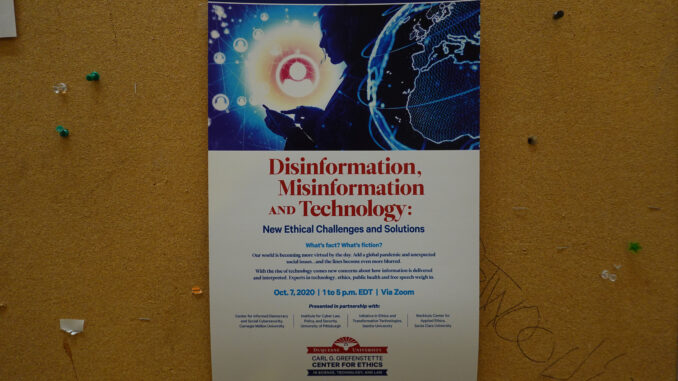

With information changing rapidly, and our world shifting more virtual, it’s only fitting for Duquesne’s Carl G. Grefenstette Center for Ethics in Science, Technology and Law to hold a symposium via Zoom discussing misinformation, disinformation and technology.

The inaugural symposium, held on Wednesday, Oct. 7, featured speakers from Duquesne, Carnegie Mellon University, the University of Pittsburgh, Seattle University and Santa Clara University, who shared their expertise on ethical challenges and solutions involving disinformation and misinformation.

Brian Green, the director of technology ethics at Santa Clara University, defined misinformation as false information that may or may not be intentionally deceptive; and disinformation as false information that is intentionally deceptive, in his keynote speech entitled “Building Communities of Trust.”

“Disinformation intentionally misleads people in order to lead them into error,” Green said. “It has a harmful element to it; you’re trying to harm people ultimately.”

Green said that it destroys trust and groups and weakens target groups in power competitions. Unlike disinformation, misinformation can be unintentional, and cannot split communities apart, he said.

“Asking the purpose of misinformation is a bit of an odd questions because in one sense; it’s like asking the purpose of a piece of trash in the information ecosystem: where truth ought to be prized, misinformation ought to be tossed out,” Green said.

One way to stay vigilant of misinformation and disinformation, Green said, is to have real relationships and experiences with people. “Try not to spend more time online than in real life,” he said.

Kathleen Carley, a computer science professor at Carnegie Mellon University, said that disinformation has always been with us, and that the concept of disinformation has many faces. “Computers are neither the problem nor the solution in this case – people are the problem,” Carley said.

She cited data that reports that 77% of the time, people in the U.S. are rebroadcasting messages by others in the U.S. spreading disinformation, and 80% of messages retweeting disinformation sites are from bots. In social media, Carley said that there are three concepts to understand disinformation: super-spreaders, super-friends and echo chambers.

Carley said that disinformation starts with a controversial issue, and bots and trolls are embedded on both sides. They foster fear with disinformation that feeds worry and send messages with URLs to disinformation sites. Like the Reopen America rallies in April in May, they call for protests, and spread disinformation about key leaders on the opposing side.

As citizens, our role in combatting disinformation is to call it out and not to spread it, Carley said.

The symposium touched on disinformation’s impact on politics, media, COVID-19 and economics. David Danks, a professor at CMU and Michael Colaresi, a professor at Pitt, discussed the political dimensions of disinformation, and the real-world consequences it has on political discourse.

Beth Hoffman, a professor at Pitt, noted that we are fighting an infodemic as well as a pandemic. An infodemic, she said, is a rapid and far reaching spread of both accurate and inaccurate information. She noted the Plandemic video with discredited doctor Judy Mikovitz went viral this spring and was shared by many people who do not normally share conspiracy theories still shared it.

Pamela Walck, a journalism professor at Duquesne, compared media coverage from the Spanish flu epidemic of 1918 and the COVID-19 pandemic today. Newspapers at the time of the Spanish flu epidemic were not writing about hoaxes, but instead had advertisements hawked as “sure-cures” for the flu, and “advertorials” – advertisements disguised as news articles.

The solution to misinformation, according to Walck, is to arm ourselves with media literacy knowledge, be aware of our own biases, be skeptical of information before sharing and be part of the solution.

Michael Quinn, the dean of the college of science and engineering at Seattle University, along with Jane Moriaty, a law professor at Duquesne, noted the economics and ethics of misinformation. Quinn noted that responsible information consumption consists of understanding the information flow and confirmation bias.

People should skeptically judge news, he said, and question the authority of the author, the reliability and verifiability of the content, the soundness of the argument and the affiliation of the site. To conclude the symposium, Duquesne President Ken Gormley said the event was a “thought provoking afternoon.”

“We’re so honored to have been able to collaborate with truly some of the most elite institutions, academic centers dealing with technology and ethics in the United States at CMU, Pitt, Santa Clara and Seattle, and thanks finally to a wonderful audience who joined us virtually and stuck with it for the afternoon,” Gormley said. “We hope that next time we’ll be able to gather here in person in Pittsburgh on our beautiful Duquesne University campus.”

In an email Gormley sent to all students on Oct. 5, he said that this event was the first of three in three weeks to engage our entire campus community in an ethical kind of thinking. The second event, titled “The Rooney Rule and What’s Next: Equity and Access in Athletics and Beyond” will take place on Thursday, Oct. 15 and the third event, “Politics, Contentious Elections and Civil Discourse,” will be held Wednesday, Oct. 21 on Zoom. The events are free, but registration is required.