08/23/2018

Hallie Lauer | Features Editor

With the recent push toward removing plastic straws from coffee shops, it’s no wonder that the search for other ways to eliminate plastic pollution has taken off. That search has also made its way to Duquesne.

Sophomore biomedical engineering major Karli Sutton, along with Professor Benjamin Goldschmidt, created a successful 3-D printing recycling system. Their system allows for the breakdown of previously printed objects to be reused in the printer.

The process starts with a prototype mechanism, designed by Sutton, that grinds the plastic from the previous prints into semi-uniform pellets and a sifter to ensure that nothing too big comes through. These pellets were then put into the Filabot EX2 extrusion system, which is the machine that extracts the plastic filaments to be the proper diameter for the print.

This prototype consists of materials such as a tractor’s steering wheel, filing cabinets and a Ninja blender.

Sutton printed the first item, a moldable wrist bracelet, using entirely recycled material on July 19.

“This is the first system of its kind to be able to use strictly recycled 3-D prints to create usable, and printable filament,” Sutton said. “The other systems on the market require virgin pellets of the material to be added in order for it to be extruded correctly. This is a huge breakthrough because it means that no new plastic needs to be introduced to the process.”

Although the plastic used in their 3-D printing was biodegradable, it still took about six months to break down, which means most of it ended up in the waste disposal system, creating more trash.

“Prior to this summer, there was no way to reuse the failed 3-D prints that were filling up trash cans in the hallway of Libermann, so they were just going to be thrown out,” said Sutton.

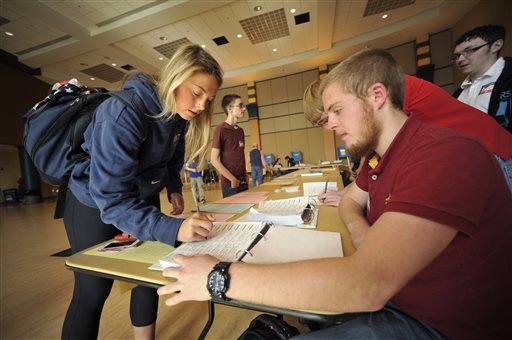

Sutton presented her findings at the Undergraduate Research Symposium on campus this past July.

This success not only helps the environment, but it is also helpful in furthering Goldschmidt’s research. When new professors are hired for research, they receive startup funding to go toward purchasing equipment. This money is specifically given until the lab can receive grants to sustain the research.

When Goldschmidt accepted the teaching position at Duquesne, he decided to 3-D print as much of his equipment as possible as a way to reduce overall costs.

“However, 3-D printer filament isn’t free and the exact formulation of plastic isn’t as controllable as would be ideal in an academic lab,” said Goldschmidt.

Thus, the research began. And as it went on, Sutton and Goldschmidt took their findings to other on-campus organizations to spread their developments.

The first collaboration was with the campus organization Pure Thirst. This organization holds the annual Water Walk and sends students to Okakola, Tanzania to help improve water quality.

The overall goal of the partnership was to develop a method to print fluoride removal filters and other systems that would clean the over-fluoridated water in Okakola.

They also paired up with the occupational therapy (OT) department to work toward a common goal.

Each semester, a student from the OT department gets paired with a student from the biomedical engineering department (BME) “to design and 3-D print assistive devices for people with low grip strength, such as the elderly. Through these projects, I realized that we were going to need a lot of customizable filament,” Goldschmidt said.

“Eventually, the goal is to turn used plastic bottles and cups into usable filament to create biomedical devices in the future,” Sutton said.

For now, their next step is to engineer a way for a motor to grind the plastic into pellets. With a motor, a person won’t have to manually grind it.

“We also plan to take the system to A-Walk during events like Duquesne Fest, or the Pure Thirst event, to have a live demonstration by using plastic trash generated from the events,” Sutton said.

They also hope to take it to local schools to allow students to get involved with biomedical engineering and the STEM field.