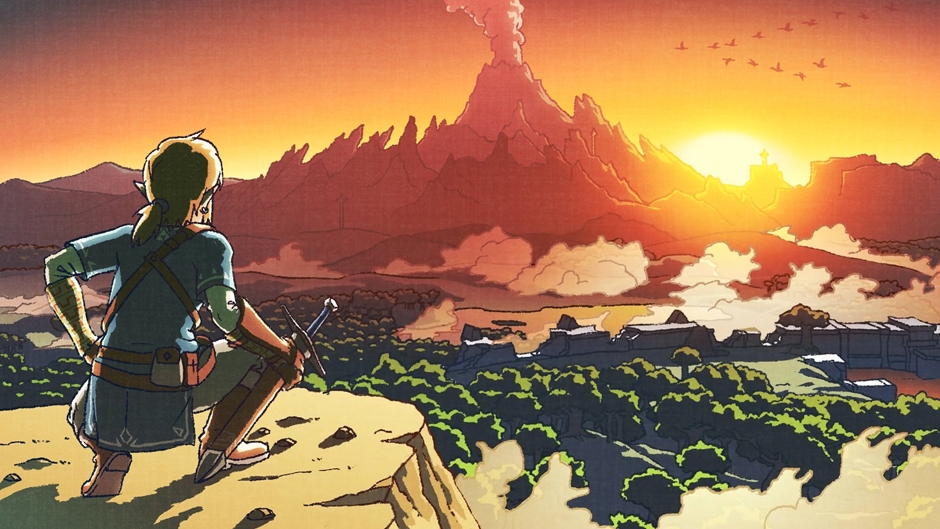

This promotional art mimics the same art used for the original “The Legend of Zelda” on the Nintendo Entertainment System. Both games are praised for their hands-off approach to gameplay.

By Zachary Landau | Staff Writer

I would not be the man I am today if it was not for “The Legend of Zelda.” I don’t say that in some sort of sappy, wholesome way. I mean this in the “this is the series that gave rise to the cynicism and bitterness that binds me to this mortal coil” way.

In those younger, more vulnerable years, I was burnt on “Skyward Sword.” What was meant to be the 25th-anniversary celebration turned out to be a mourning that crushed my “Zelda”-filled heart.

In the midst of my despair, I thought “The Legend of Zelda” would be better off as a full, roleplaying game. I eventually abandoned this thought, however, not only because I grew as a person, but because an RPG “Zelda” game would, in essence, not really be a “Zelda” game anymore.

It was that thought that stirred in my head while playing “Breath of the Wild.” While traversing the open plains of Hyrule, I could not help but think that I really was not playing a “Zelda” game, but instead an amalgamation of open-world games with a bit of Nintendo magic sprinkled here and there.

To be certain, all of the “Zelda” trappings are here: Link, Zelda and Ganon all take their respective positions of Hero, Princess and World-Ending Evil, and races and locales from past games make cameos and appearances as well. And if one were to follow the main quest, the overworld-dungeon-repeat cycle is still present, with the dungeons being, in my opinion, the best in the entire series.

What is different is everything else. The overworld dwarfs other games in the series (and most games in general), but feels very much alive and, to use the trite phrase, lived-in. At any moment, players can come across Bokoblins ambushing travelers or a dragon weaving in and out of mountain tops. Every NPC and enemy is crafted with enough detail to be impressive on their own.

Traveling this world, unfortunately, can frequently drag and bore. Horses, which are the fastest form of transportation after teleporting, frustrate players with their controls and frequently freak out when even grazing the occasional hanging tree branch. Not only that, their usefulness remains questionable even after 50+ hours, as most points of interest are hidden within mountains and cliffs where horses cannot explore.

Traversing the many ranges of Hyrule is also made a huge pain by the hateful, spiteful return of the stamina meter as well. Nearly every action Link does requires Stamina: running, climbing, gliding, charging attacks and even swimming. The amount of Stamina given to players at the start of the game is pathetic; Link can only run about 30 meters before exhausting himself. After a few hours into the game, players can grab their first upgrade for the Stamina Meter, but even then, the upgrade is so minimal that it was not until I reached the 25 hour mark that I felt like I could cover some significant distance in one bound. While there are a lot of interesting things to explore in the overworld, constantly monitoring stamina discourages exploration for most of the game.

Unfortunately, the main quest can be rather unexciting at times and a hassle to complete. While dotted with the occasional interesting or funny character interactions, the mini-plots within the different chapters are rather trite and cliché. What emotional depth there is could not drown a mouse and almost parodies itself in how ridiculously stoic the characters are. At one point, Link tells a guy his daughter died (yes, that actually happens), and he reacts the same way you might if someone ate your lunch in the break fridge.

That’s not to say emotionally charged moments do not occur in “Breath of the Wild.” The unlockable Memories are fantastically directed cut scenes that add real characterization for an otherwise forgettable cast. They also effectively motivate the player by egging them into restoring Link’s power by demonstrating his skills and prowess. What particularly caught my attention was how most of this characterization is implied: Sure, Zelda may occasionally comment on how much Link is growing, but rarely in Memories do characters blatantly describe each other and themselves. Instead, the game is comfortable showing the duo walking calmly away from piled up corpses of recently felled enemies without commenting on the devastation they just caused. This subtlety is lost in the main cut scenes, however, and characters tend to talk in very plain, simple language and extrapolate on the entire plot in long, tiresome monologues. I have a suspicion that two different teams dealt with optional and required content, as the optional content is far better than the required.

This quality is reflected in the aforementioned dungeons, which, as previously mentioned, are the best in the series. Despite their smaller size (the smallest dungeons in other “Zelda” games are bigger than any of the four in “Breath of the Wild”), these dungeons tightly pack spatial puzzles that present the perfect level of challenge to make players question and ponder without having to resort to outside help. The boss fights leading up to the dungeons are truly epic and thrill in their grand scale and speed. The only disappointing parts about dungeons are the bosses at the end of them and their optional nature, meaning some players may miss them entirely. And a “Zelda” game without dungeons really isn’t a “Zelda” game, is it?

This is why I feel rather confused about “Breath of the Wild.” The parts that more closely resemble the franchise it hails from are without a doubt the best. However, the extra stuff, while exciting for some, only bothered me in how obtuse it made the game. I do not regret my time spent with “Breath of the Wild,” but I also do not imagine myself returning to the game anytime soon.