By Carolyn Conte | Duquesne Duke

Coming out of an area rife with struggle, “She Who Tells a Story” – a new installation at the Carnegie Museum of Art – reveals a glimpse into the lives of women in the Middle East.

The exhibit, which is open through Sept. 28, gives a powerful look into the lives of women in the Middle East and the many challenges they face. The photographs of Arab women, by Arab women, brought attention to the pressure for unheard and unseen women in their homes, others captured the relationships separated by war, while the relatable side of Arab women was also featured by some. Each of the 12 photographers stick to a different theme in their series, revealing a new perspective to viewers. The exhibit challenged opinions of Western estrangement from Middle Eastern women, but also portrayed the struggle against violence many face.

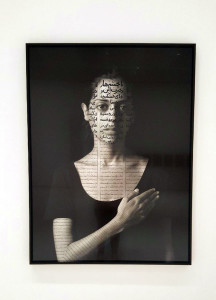

A solemn woman with her hand over her heart is depicted by Shirin Neshat, an Iranian who is known for addressing the Arab Spring, nationalism and the interaction of masses, according to information given at the exhibit. Newsha Tavakolian, also from Iran, demonstrates a theme of communication. Her series “Listen” offers portraits of Iranian singers. Most striking of Tavakolian’s collection are the titles of her pieces: “Don’t Forget This is Not You,” “When I was 20” and “Again I stayed behind in the Empty Cold” all of which are featured at the exhibit.

Photo by Carolyn Conte

Another photographer in the exhibit, Boushra Almutawakel, reveals the erasure of identity as hijabs have become less colorful in the trends of her home in Yemen. A line of pictures, beginning with a smiling woman in a white hijab, ends with a depressed woman clad in black. Almutawakel’s “Mother, Daughter, Doll,” a series of nine inkjet prints, ends in all three being not only draped in dark colors, but their faces themselves are darkened.

In contrast, Iran’s Shadi Ghadirian photographs women in ironic poses and in a comedic light. Her “Qajar” series features women with forbidden objects like a Pepsi or sunglasses, in masculine, confident or even chill postures. This series is worthy of attendance for its clever humor and that it “westernizes” the subject for the visitor to consider Middle Eastern women outside of the stereotypical box.

For those looking to grasp the suffering of others better, Rula Halawani from the West Bank and Gaza Strip presents the turmoil of her homeland in her work of negative photos capturing people in their destroyed homes. Though from Jordan herself, Tanya Habjouqa also covers the Israel-Palestine conflict, in her “Women of Gaza” series.

Jananne Al-Ani, from Iraq, comments on the history of military surveillance in the “Aerial I” series of photos taken from a plane, while Iran’s Shadi Ghadirian interrupts comfort in her images of public pleasures versus private desires. A helmet is hung next to a vibrant cloth, heels rest next to boots and a fruits basket includes a grenade in her series “Nil, Nil.” This series is notable for its reminder that dreams are not forgotten by war, and that war is a part of daily life for many.

Meanwhile Rana El Nemr from Egypt angled her work about the rapid changes and anonymity of life. “The Metro Series” displays women on the metro. It questions the universal sense of belonging to strangers adjunct to our similar displacement. For people who enjoy contemplation, this is a great series at which to spend time.

One of the more interactive components of the exhibit is the wall of impressions to which viewers may contribute. On this, one could tell the most popular set was Rania Matar’s (Lebanon) “A Girl and Her Room” series. It certainly provoked the most commentary on the wall of responses.

Photo by Carolyn Conte

“This photograph does an excellent job of showing that media images of Arab women are one-sided portrayals that serve a narrative of knowledge and power. It is easy to consider Arab women as oppressed and in need of saving; it’s surprising to many that Arab women are more alike to their Western counterparts than the media says,” Sarah Khallbuss of Pittsburgh wrote on the wall.