Zach Landau | A&E Editor

11/16/17

David Cage is a hack. There’s just no other way to describe someone so tone-deaf and so pitifully, woefully incompetent as him.

But if you’ve been hanging around in games media for a while, you probably already know that.

See, on Oct. 30, Cage touted his and Quantic Dream’s latest game, Detroit: Become Human, at Paris Games Week. In the trailer shown off during Sony’s conference, audiences were treated to a slice of the game where the player character is the victim of domestic violence. The scenario, meant to model how other events will take place in the game, demonstrates the branching paths of choices players can make to lead to different outcomes, including how this scene will play out.

If just the mere description of that instills a vague sense of disgust in your soul, then we’re on the same page, baby. But hang in there; it’s going to get worse.

After the conference, Cage attempted to defend his decision to show a man beating a woman by claiming that, as a writer, he needed to explore the issue because it made him feel emotions.

“When you’re a writer, you talk about things that move you, that you feel really deep inside you that’s something that moves you, and you hope it’ll move people, too,” Cage said.

Well, that settles it then. I guess Cage is off the hook.

I’m kidding, of course.

Kara, one of the primary protagonists of ‘Detroit: Become Human’, is controlled by the player during the incident shown in the PGW trailer.

There’s so much wrong with this whole Detroit fiasco that I honestly can’t believe that no PR manager at some point didn’t say, “Hey, maybe we shouldn’t show this scene where a father beats and kills his daughter without context to thousands of people on an international stage.” That should be the end of the discussion: It was in no way, shape or form appropriate to show that footage at a conference like Paris Games Week. The only saving grace is that the stream for Sony’s conference and the subsequent trailer are age-restricted.

However, let’s consider the appropriateness of putting this content in the trailer in the first place. Let’s pretend that Quantic Dream actually had a modicum of sense and decided not to release this trailer at a conference and just on its own, with a warning in advance that it contains explicit material. Let’s pretend that was the case; it would still be wildly inappropriate for domestic abuse to feature in a trailer marketing a game.

Why? Well, for a number of reasons, but let’s just make something clear before we really get into this: Games should absolutely explore complex and difficult issues. No one is disputing that, especially not I. If it were not for my ardent belief that games are a legitimate art form, I would not be wasting my Sunday night writing this piece. Got it? Good.

Let’s start with why someone would decide to include this content in a trailer. If we believe that the explicit purpose of a trailer is to convince potential buyers to buy a game by showing off attractive features of said game, what feature exactly is being shown for Detroit?

Is it the writing? It better not be, ’cause that is some of the most abysmal writing I have ever heard. As games commentator Jim Sterling, in his column “Detroit’s Domestic Abuse Trailer Is A Hackneyed Farce,” astutely calls out, Cage’s writing is, “like those melodramatic made-for-TV movies with cartoonish [sic] abusers and overtly choreographed violence that borders on action sequences.” Cage’s pathetic and grossly insensitive writing clearly demonstrates just how out-of-touch he is with reality.

Is it the graphics? Again, hopefully not. The game doesn’t look bad by any means, but it isn’t considerably more impressive than Cage’s past work.

So all that’s left is the gameplay, and here is where the stickler lies. The purpose of this trailer is to demonstrate the choices available to the player throughout the game. Do you choose to run or to barricade yourself? Do you escape or do you confront the abuser? “Your choices matter!” the nagging voice in the back of your head says. “Try taking the gun with you next time!” it continues.

“If you made the right choices, you wouldn’t have been beaten by Todd,” it implies.

See the issue here? Games, almost uniquely as an artistic medium, involve audience choice, and by including a scenario where the player is the victim of domestic abuse, you have to take into consideration of what it means to give players choice in this scenario. The messages are you sending by giving players agency in a real-life situation needs careful consideration.

Or, as writer Meg Jayanth said on Twitter, “I cannot imagine anything more offensive than implying that there’s some kind of choose-your-own-adventure escape from domestic abuse.”

Scott Benson of Infinite Fall also lambasted Cage for using domestic abuse as a feature, comparing it to advertising the specs of a title.

“Cage went with that trailer because he expected the content to impress you, to blow your mind, to make you think it’s brave, to shake you,” Benson said in a Twitter thread. “[Because] Cage is part of a generation of games folk who think that emotion and trauma and Big Serious Things [sic] are like 60 FPS or antialiasing [sic].”

The content of the trailer is meant to communicate that games can be a serious art form, Benson continued. Of Cage’s Eurogamer interview, Benson said, “That is just an embarrassing read. We are SERIOUS ARTISTS JUST LIKE FILMMAKERS AND AUTHORS.”

By choosing to show choices without the framing of the rest of the product, to take a slice of an artistic work and present it to the world, Cage is using domestic abuse as a selling point for his game. It isn’t an issue being discussed (and this is by his own admission. In the same Eurogamer interview: “The game is not about domestic abuse”) but a framing device for players to exercise their choices.

“Choice — or the absence of choice — is as important to game narratives as editing is to film,” games writer Bruno Dias explained in a column “I Don’t Trust David Cage to Tackle Domestic Violence in Detroit.”

“Every time you give the player a choice, you give them agency,” Dias continues. “But the flipside of agency is responsibility, complicity. When you put the player in the shoes of a domestic abuse victim and then represent their struggle as a series of gamebook-style choices … you are suggesting that domestic abuse victims are complicit in their own abuse.”

This is to say nothing about Cage’s dismissive attitude of his control in the writing process. To act like putting domestic abuse into Detroit was some act of the Muses of video games just flies in the face of not only conventional wisdom (no one forced you to do this, Cage), but also undermines Cage’s status as a writer.

As Dias also states in his column: “[The implication from the interview is that Cage] didn’t set out from the start to tackle domestic violence. It just came up.

“There’s nothing wrong with that, but that is still a choice. You have to own that choice,” Dias added.

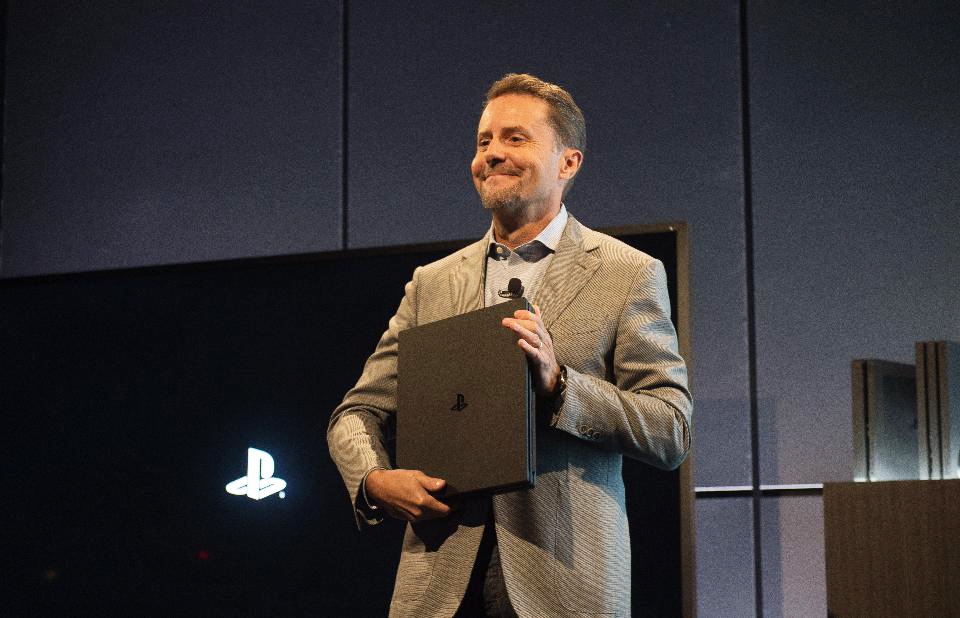

David Cage, pictured, founded Quantic Dream in 1997. His writing credits include ‘Fahrenheit’, ‘Heavy Rain’ and ‘Beyond: Two Souls’.

But the most worrying thing of all is that Cage’s bullheadedness isn’t new. It’s a known matter in games press that Cage is more interested in (whatever he believes is) advancing the medium as a respected form. However, the writer has not the first clue what it means to be an artist, and at this point, it is cringe-worthy to even pretend that he is one.

The most infamous part of the interview comes toward the beginning of the conversation, when Cage stubbornly — almost childishly — retorts, “Let me ask you this question. Would you ask [why did you decide to show domestic violence in a trailer] to a film director, or to a writer? Would you?”

Now, I would first like to praise Martin Robinson for not immediately spitting in Cage’s face for asking such a disgusting and unprofessional question and implying that Robinson’s credentials as a journalist are dubious. He clearly has the patience of a saint.

But Cage’s hissy fit is indicative of an attitude that he has exhibited for a decade now: He demands to be respected as an artist. He doesn’t believe he has to earn it; just simply acting like directors or novelists should be deserving of respect in his view.

Reading his interviews, however, it becomes abundantly clear that Cage is nowhere close to being an artist, not even an amateur. No artist would deflect criticism by claiming that they’re being singled out. No artist would so poorly explain their choices in a given context as well.

In a GameSpot interview from Oct. 31, Cage demonstrated a similar ignorance as to what makes great stories great. There’s no one moment to point to in his lengthy, rambling and often-contradictory answers that truly encapsulates the problem with Cage, but reading them makes his deficiencies clear as day. Cage has no critical theory background; he acts like the audience putting a part of their lived experience into art is some revolutionary concept and not something academics have been debating for decades, maybe centuries.

“My role as a creator is not to tell you what you should think, right?” Cage asks Tamoor Hussain, completely divorcing himself from any responsibility in the work that he produces.

“I think Detroit is going to ask another question that is going to be very interesting: Is a video game legitimate to talk about anything, or not?” he also ponders, the veritable Socrates of gaming that he is.

Except not. What Cage can’t wrap his head around is that the mere act of creating is meaningful. He already answered his stupid, inane question by the mere fact that he put those issues into the game already. We have to talk about domestic abuse because he put it in there.

Why are we wasting time explaining how basic reality works to this man?

No one in the past two decades has questioned the validity of games talking about major issues, at least not in the industry itself. Games like Silent Hill 2, Majora’s Mask, Braid, Bioshock and many others have answered Cage’s question, time and time again. For him to act like he is some avant-garde in the medium is shameful and conceited, especially in an industry packed full of fantastic writers and artists who have told “meaningful” stories for longer than Cage has been moaning about “emotions.”

Games have gone way past simply asking whether or not they can talk about real life issues — that ship has sailed. Now, the conversation is how games handle those issues, what type of merits do their messages have. And that’s why people — myself included — have come down so harshly on Cage. The actual frontier of games lies not in whether or not we can show a child being abused, but in asking what is the importance in doing so. Why is it important that a character must endure something as horrific as domestic violence? Why is it appropriate to use a real-life tragedy as a means to carry a mechanic? What does simply showing such a horrific and vile event really mean?

And Cage, resoundingly, has no answer for any of these questions.