By Catherine Clements | Student Columnist

“You’re studying abroad in Italy, do you know any Italian?”

“No. I can survive without it.”

Shocking as this conversation may be, it is the harsh reality for most Americans. The way we look at foreign language education is egocentric. We do as little as possible and expect the rest of the world to meet us where we are. More often than not I hear people say, “Why do I have to know (insert foreign language here) if everybody speaks English?”

Education in the United States puts minimal value on foreign language education. Currently, there is no national standard for the study of foreign languages. Instead, it is up to each individual state. According to the Digest of Education Statistics, the average high school student only receives two years of foreign language education.

Across the globe, foreign language education begins in elementary school or earlier. The entire European Union, except Ireland and Scotland, require at least one, if not two, foreign languages to be taught in school.

U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan pointed out that only 18 percent of Americans report the ability to speak another language, while 53 percent of Europeans (and growing percentages in other parts of the world) can speak at a conversational level.

“Language learning facilitates communication between peoples and countries, as well as encouraging cross-border mobility and the integration of migrants,” said Androulla Vassiliou, commissioner for education, culture, multilingualism and youth in the EU.

I began learning French in the ninth grade. Five days a week, I had French class for 50 minutes. After four years, I picked up a lot but in no way mastered the language. Now, I feel like it is “too late” for me to learn another language. By not speaking a second language, I am limited in my future opportunities.

I may have missed out on becoming proficient in a second language, but it’s not too late for future students. How can we build a successful foreign language education program for them? How can we compete with the increasing numbers of bilingual speakers around the world?

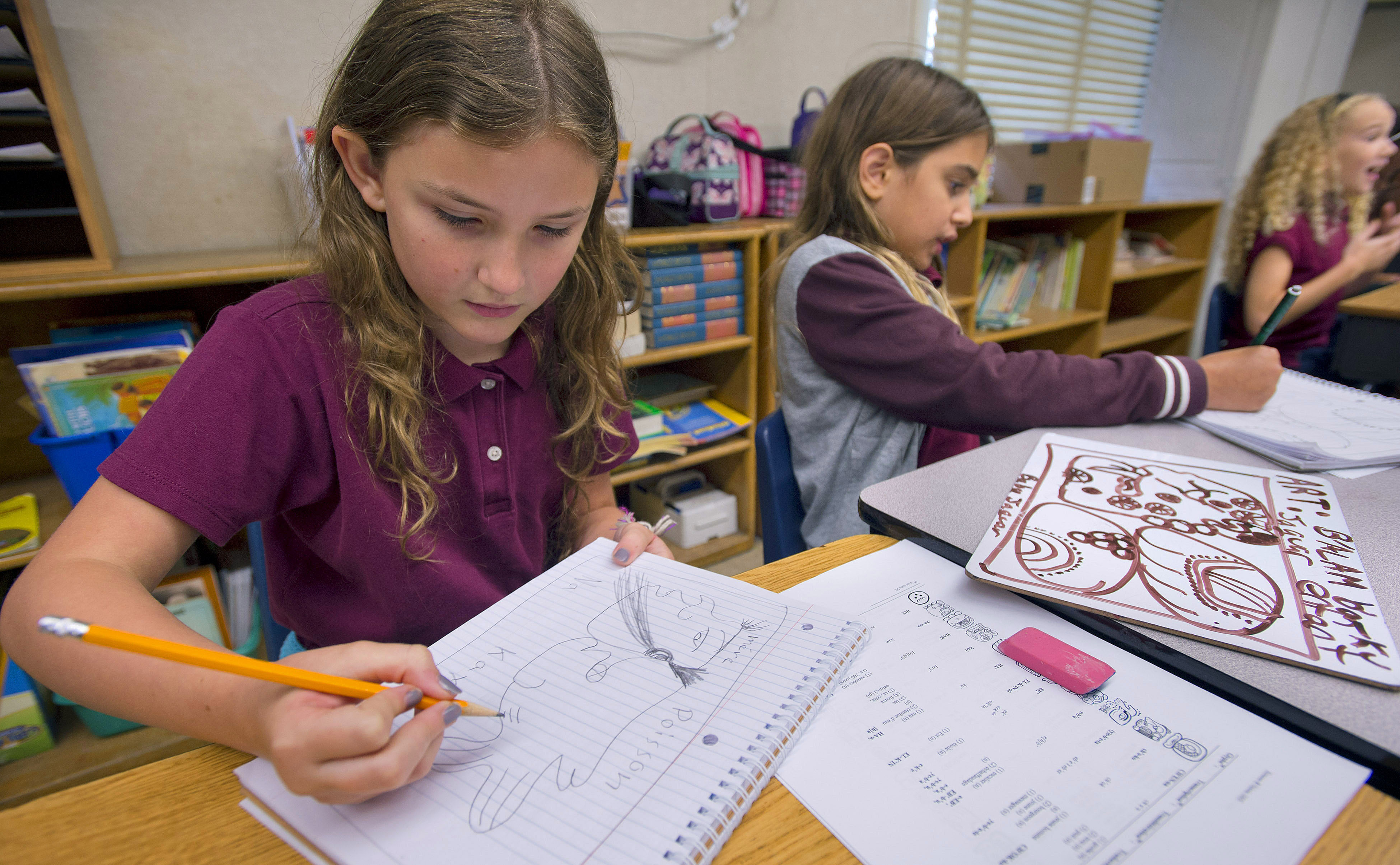

The answer is dual-language classrooms. Teaching students as early as preschool how to speak a second language is vital in today’s world. Schools are now beginning to implement programs where lessons are divided between English and a second language. 50 to 90 percent of the school day is taught in the target language. Some schools switch languages halfway through the day, while others alternate by day or subject.

New York City has seen an expansion of dual-language programs in the recent year. This fall, 39 programs were implemented, totaling about 180 programs city wide according to the Department of Education.

What’s surprising is it’s not just the Spanish language that schools are implementing. Arabic, Chinese, French, Haitian-Creole, Hebrew, Korean, Polish and Russian programs can be found throughout New York City schools.

In an interview with The New York Times, Libia Gil, assistant deputy secretary and director of the office of English language acquisition at the federal Education Department, said, “There are clear indications of a movement [towards dual-language classrooms].”

The New York Times stated that dual-language classrooms may take longer at first to match the grade level in the foreign language, by late elementary school and middle school students do just as well – if not better – in school overall. Students are even more likely to be seen as proficient in English. Basically, not only our students improving their second language skills, but their English skills as well.

It appears the Department of Education is finally valuing the importance of foreign-language education. With such a global economy, language education is a necessary step to provide opportunities for future generations.

John B. King Jr., a senior adviser for the federal Education Department and soon-to-be acting education secretary for President Obama, told The New York Times that dual-language programs “can be a vehicle to increase socioeconomic and racial diversity in schools.”

It’s not just big cities like New York that are adopting these new programs either. Utah and Delaware are both launching statewide efforts to improve and create dual-language classrooms.

Gov. Jack Markell of Delaware states he wants two things: “I want students from Delaware to be able to go anywhere and do any kind of work they want to do, and I also want to attract businesses from around the world, to say, ‘You want to be in Delaware because, amongst other things, we’ve got a bilingual work force.’”

With such a competitive job market today, proficiency in a second language will make applicants more marketable. Speaking a second language opens students up to a world of possibilities whether it’s working abroad or domestically.

Last semester, I studied abroad at Duquesne’s Italian Campus in Rome. Studying abroad made me realize how interconnected the world actually is. It also made me realize how embarrassed I was to only speak one language. Interacting with people who could speak two, three or even four languages made me wish my schooling had been that comprehensive.

However, educators are hesitant about the drawbacks of dual-language classrooms. I don’t blame them; for the United States, it is a very new idea. Hiring qualified teachers and developing well-run programs are keys to its success. Some educators fear that with the implementation of a second language, standardized test scores will decrease.

But isn’t more beneficial for students to have the ability to speak a second language? Or, couldn’t a second language be a part of a standardized test? It disappoints me that what’s holding us back is scoring well instead of actual learning.

Dual-language classrooms will diversify our schools and produce better educated students. Dual-language schools are the way of the future, and I hope we will see more growth in the next several years.