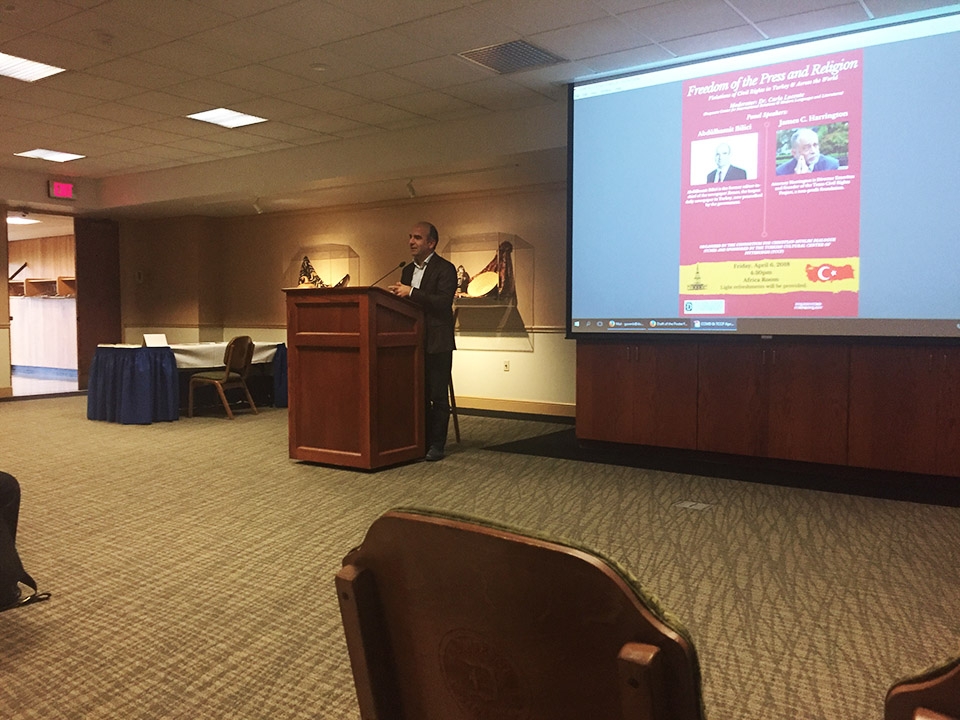

Abdülhamit Bilici speaks to Duquesne about the current repression of the press in Turkey.

Abdülhamit Bilici speaks to Duquesne about the current repression of the press in Turkey.

Hallie Lauer | Layout & Features Editor

04/12/2018

In a time when freedom of the press is contradicted by governments across the globe, Abdülhamit Bilici, the former editor-in-chief of Turkey’s largest newspaper, told his story of March 4, 2016 — the day his paper was taken over by the Turkish government.

For this panel discussion on April 6, Bilici was joined by attorney James C. Harrington, the founder of Texas Civil Rights Projects (TCRP). TCRP is a legal advocacy organization for low-income peoples in Austin.

The main topic of Harrington’s speech was the importance of opening up a dialogue about civil rights.

“We are not at this point building civil society; we are undermining it. [We are] moved toward a sense of individualism that trumps community,” Harrington said. “Excuse the pun. We have got to change the narrative. If you’re going to have human rights, you need community, civil liberties and civil rights.”

Harrington went on to address the differences in the way America treats civil rights and liberties compared to other countries.

“In South Africa, healthcare is a right; in the U.S., it’s a privilege. A privilege that the government can take away whenever they want, and that’s what they’re doing,” Harrington said.

Bilici then took to the podium to tell his story. He was the editor-in-chief of both the English and Turkish versions of the paper, Today’s Zaman. On March 4, 2016, the paper was taken over by the government, all its archives were deleted and is now in the governments control.

In the summer of 2015, there were protests in Turkey, and much to the surprise of the Turkish people, the government shut them down brutally. The government began denouncing journalists and media outlets that reported the truth and were critical of the government.

“Journalists who continued to be critical lost their jobs. While these protests were happening, the U.S. CNN was broadcasting the protests and CNN Turkey was broadcasting a documentary about penguins because the government was calling,” Bilici said.

Bilici’s paper reported the events as they happened. It stayed true to its editorial policy of fighting against fake news and creating dialogue within differing groups of society.

Throughout the next year, government officials would cancel press cards for reporters at Zaman, increase visits from the tax inspector and call businesses to convince them not to buy ads.

“We had an office for our tax inspector, he was there so often,” Bilici said.

“[I am] a person who witnessed what it means to lose democracy, to lose human rights, to lose media,” Bilici said. “It is unimaginable in your country [and] in your minds.”

W

With those words, Bilici showed a YouTube video titled “Brutal Government Takeover of Turkey’s Largest Newspaper.”

“[With]in 24 hours, it became a mouthpiece of the government,” Bilici said. “Circulation went from 700,000 to 5,000 in a week.”

In the week after the shut down, the government labelled Bilici a terrorist. He then fled to first Europe and then to the U.S., later bringing his family with him.

“I am a journalist in exile now. Despite that I feel fortunate. I am safe and free now in this beautiful country,” Bilici said.

But that is not true for all who worked with him. According to Bilici, Turkey is number one in terms of journalists in jail, and 90 to 95 percent of the media is controlled by the government.

“[This is] why I speak on such platforms now. It is the only thing I can do to help my friends back in jail in Turkey,” Bilici said.

“This was the frontline in democracy. They destroyed that frontline; you are not safe, not even in Pittsburgh,” he said. “When you are not able to protect that frontline, you are not able to protect yourself. It is not freedom of journalists, it is freedom of you … This is a huge loss for the whole world.”

Bilici’s final parting words were of warning to the U.S.

“Be cautious, but optimistic, of the trends here,” Bilici said.