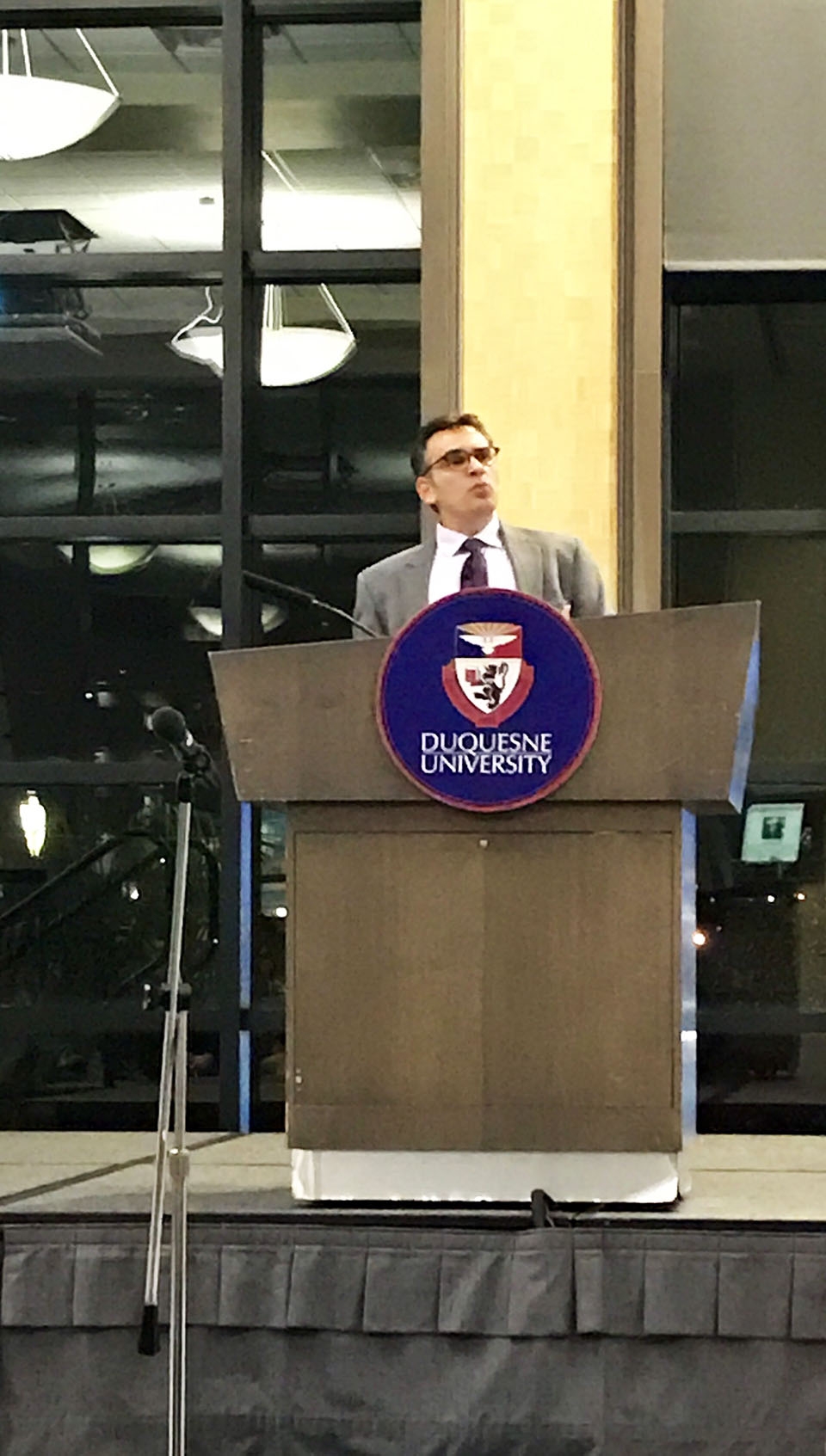

Michael Neiberg, a professor and author from the U.S. Army War College, presented on the build-up to America’s entry into World War I. Neiberg is a renowned expert on the war.

Michael Neiberg, a professor and author from the U.S. Army War College, presented on the build-up to America’s entry into World War I. Neiberg is a renowned expert on the war.

Raymond Arke | News Editor

America was in crisis. Threats of immigrants, border friction with Mexico and a meddling European power felt overwhelming. This was the scene set by Michael Neiberg, a professor from the U.S. Army War College, as he discussed America and its entry into World War I as part of Duquesne’s 51st consecutive History Forum on Oct. 23.

The annual forum, presented by Duquesne’s History Department, has been running since the 1960s, according to John Dwyer, chair of the department, who welcomed the crowd. It used to be a regional conference until the 1990s, when it transitioned to its current form, in which the department invites one nationally-known scholar for an evening.

The goal of the forum is to keep history in people’s minds.

“[It] shows how history is still relevant in two ways: How people’s lives change and how the past impacts the present,” Dwyer said.

John Mitcham, another history professor, was the main organizer of the event. He spoke briefly, stressing the importance of learning about the First World War, as many Americans no longer remember much about it.

Mitcham pointed out that there is no national monument in D.C. to remember the war, yet it “helped shape a new, modern American society.”

Neiberg, the keynote speaker, is one of the top World War I scholars in the country. One of his books on the war, Dance of the Furies, was named by the Wall Street Journal as one of the five best books ever written on the conflict.

Neiberg’s presentation focused on America and how the public’s feelings toward entering the war evolved from 1914 to 1917.

Initially, America and President Wilson took a neutral stance, viewing the war as a purely European affair. However, Neiberg said that the conception that Americans didn’t pay attention to the war is false.

“[Americans] absolutely were paying attention … virtually [every journalist] tried to get on a boat to the Western or Eastern front,” he said.

In particular, Neiberg highlighted the journalist Mary Roberts Rinehart, a Pittsburgh-area native, who wrote for the Saturday Evening Post. The Post made her a war correspondent and sent her to cover Europe.

Neiberg said that Rinehart’s evolving opinions on the war followed four main themes, which influenced public opinion.

“First, she went to Europe saying Europe as a whole caused this to happen. Then she gets to the Western Front and said that Germany alone caused this. Two, she said that the British are trying to trick America to get into the war,” he said. “Three, she saw early on that the U.S. may have to fight the war. And four, in 1915, she said the U.S. needs to start thinking about [entering the war] now.”

Neiberg also addressed the sinking of the Lusitania, which many people still cite as a main cause for American involvement in the war. Neiberg takes issue with this interpretation.

“The Lusitania did not cause the U.S. to enter this war,” he said. Rather, it contributed to a larger debate over whether the U.S. should be more isolationist or begin to intervene.

As the war went on, American views towards Germany and Germans got harsher and harsher, Neiberg said. He also said that the opinions deepened after the Black Tom explosion, in which two German agents blew up a New Jersey pier stocked with explosives and munitions.

“Genuine fears were beginning to develop in the United States,” he said.

Many people were concerned that not getting involved would lead to America being a bystander on the world stage.

“The argument here was that the U.S. was going to turn into China, a wealthy country picked apart by outsiders,” Neiberg said.

During the buildup to America’s entry, Neiberg said that American businessmen and companies were making quite a lot of money supplying Britain and France with war materials.

“[There were] questions on morality of profiting over Europe’s strife. What does it say about us if this is our relationship to the war,” Neiberg said.

Even as the U.S. government’s official stance was neutral, Neiberg said many individual citizens raised money for charity efforts or even joined foreign armies. One example Neiberg discussed was William Thaw, a Pittsburgher, who joined an American volunteer pilot squad in France and is thought to have been the first American to engage in air combat in the war.

Thaw, who is buried Allegheny Cemetery in Lawrenceville, joined the Lafayette Escadrille, which composed of other American volunteers, and according to Neiberg were “excellent at what they did.”

Neiberg discussed the main driver behind America’s decision to get involved, the Zimmerman Telegraph. The communication, sent from Germany to Mexico, and intercepted by the British, was a German offer for Mexico to attack the U.S., if America got involved. Germany promised Mexico the ability to reclaim the lost lands of Texas and California and also mentioned the possibility of including Japan at the bargaining table.

Neiberg said that the discovery of this offer, which Mexico refused, scared Americans.

“The war is now about the very future of the United States … Many Americans see this as a declaration of war … The fear is that the United States itself would cease to exist,” he said.

For a moment, American public opinion was close to being united and not long after, Wilson and Congress formally entered into World War I.

Neiberg said he got into studying World War I because of the lack of teachable material on it.

“I got involved in this period of history because I was so disappointed in the books that were available for teaching. This was in the mid-1990s and it seemed to me that the books were too focused on local history and on specific battles,” he said. “There were too few books that took a wider or deeper look at the war – what it meant, how it changed lives and nations around the globe, etc.”

He got decided to dive in and closely study the conflict after the suggestion of an editor.

“I was having dinner one night with the editor who published my first book, and I was complaining about this, and she said ‘If you don’t like what’s out there, write the book that should be out there.’ In retrospect, it was kind of presumptuous of me to do this, but I did, and the more I worked on World War I, the more complex it appeared, and the more questions I had,” he said.

Neiberg advised students to understand that World War I and the decisions surrounding it are very complicated and require close attention.

“In my view we have simplified this period of history way too much. Simple answers won’t cut it,” he said.

He also said that he was pleased to stop at the forum.

“I really enjoyed my visit to Duquesne. The conversation with students and faculty was wonderful,” said Neiberg. “I’m really honored to have been asked and delighted I could be a part of History Forum 2017.”

Mitcham was also happy with the event.

“I was very pleased with the evening. We had high school students, Duquesne undergraduates and graduate students, faculty from several departments and numerous members of the community. This is the purpose of the forum: to bring together a group of diverse individuals to hear a lecture on a topic of common interests,” he said.

Mitcham said that the forum is important because it serves as a link between the Pittsburgh community and Duquesne. He said it also shows the importance of constantly visiting the past.

“[The forum] demonstrates that history and our understanding of the past is something we constantly revisit and reinterpret. Last night, Dr. Neiberg laid out an entirely new way of thinking about American society and the decision to become involved in the First World War,” he said. “Some people incorrectly claim there is nothing new to be found in studying the past. The forum is an annual reminder that this claim is naive and patently false.”