Rio Scarcelli | staff writer

Sept. 23, 2021

Remembering the stink bug invasion that began in 2011 in North America is easy to do when it comes to how quickly the invasive species spread in the country. As of right now, a similar spread is happening with an invasive species known as the spotted lanternfly around the eastern coast of the United States.

The spotted lanternfly was first spotted in Pennsylvania was in Berks County in 2014.

For faculty advisor of the Duquesne Ecology Club Brady Porter, it was no surprise that the insects would be making the spread that they are today, so much so that the lanternfly has made its way to campus as of Sept. 14.

“It has been on my radar for the past five years or so as something that could arrive at any time. It has been in Allegheny County for a few years now, however this is the first time I’ve seen it anywhere around Duquesne Campus,” Porter said.

This is an insect in the order hemiptera, which translates to ‘true bug.’ A true bug has a piercing, sucking mouth part. They either specialize in sucking on plants or animals. This particular insect is a plant hopper similar to aphids or cicadas. Their mouth is used to suck the sap of plants and they seem to be most attracted to a plant called the tree-of -heaven.

Porter explained that trees-of-heaven are invasive species stemming from southeast Asia. They became the host plant for the spotted lanternflies, which was initially a good idea to curb the tree-of-heaven’s population.

Eventually, however, their spread transitioned to over 70 different species of plants crucial to commercial business including grapevines, vineyards and Maple trees, among other hardwood trees.

“This is the time of year whenever the males are in flight. By being flighted, they can locate from one tree to another to disperse eggs at a rapid pace, he said. Over the winter, they will cultivate in the form of a brown smudge that is not largely perceivable to the human eye. A lot of times, they get transported to mulch, dirt or even vehicles,” he said.

“There are around 60 counties actually under an ecological quarantine in attempts to stop the population spread,” he said.

Regardless, it has already spread to the remainder of eastern Pennsylvania and created a belt around the middle. Right now, they have gone as far as Delaware, New Jersey, New York, Connecticut, Pennsylvania, Virginia, Kansas, West Virginia and Ohio.

For Porter and the Ecology Club, a kind of spread such as this was important to raise awareness especially in lieu of spotting their first bug on campus.

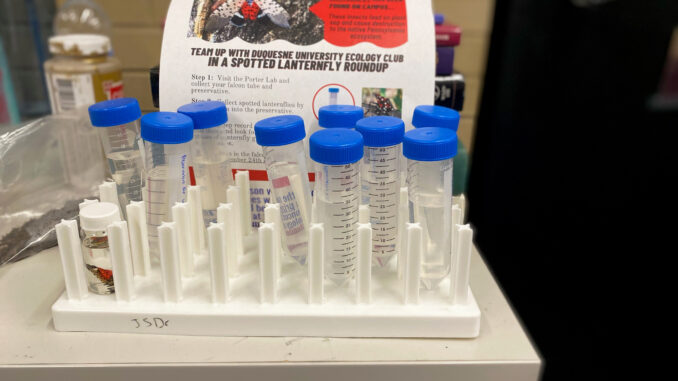

“My first sightings of the bug occurred on campus last week (Sept. 14). I was able to preserve a few of the bugs to properly examine them. That gave me the idea of creating an activity to say, ‘let’s promote awareness for the lanternfly and see how many we truly have on campus.’ I wanted to get collections of as many as we could and make it a sort of incentivized contest. Every one preserved is one less that can reproduce. I feel by doing this it will certainly knock down the population on campus at least slightly,” Porter said.

The bugs, Porter speculated, are beautiful in nature. Unlike an invasive species like stink bugs that acted as more of a nuisance to people around them, the Spotted Lanternflies do not pose any innate threat to human beings. Because of this, their population was able to persist and spread as long as it did.

“Generally, they go on without people being aware of them, and I think that is why we are trying to promote awareness. Getting people out to see these things can allow individuals to keep an eye out for them. If we can do that, we can make efforts to find localized places to eradicate the eggs and preserve nature within campus,” he said.

It is because of this that the Ecology Club will put their plans into action with their contest intended to keep the Duquesne population density at bay.

“We have sent out a contest to the Ecology Club members and people of any major to give them an understanding of our personal environment. This specific mission has been displayed throughout Mellon Hall monitors and posters in various locations,” Porter said.

“In order to participate, you get a tube located outside of room 233 of Mellon Hall filled with preservatives that can be taken out for up to two weeks.”

“This Friday, Sept. 24, you can count the amount of bugs you have captured in your tubes. The person with the highest number of bugs gets a prize that is conveniently a battery-powered lantern,” he continued.

Though the competition ends this Friday, the effort can still be maintained for students across campus as long as they like. The efforts made, no matter how small, are something Porter and the Ecology Club hope to instill within Duquesne students.

“I think now that the bugs have been established in the county, we are probably going to have to deal with them long-term. Still, we do not have to put up with huge populations on Duquesne’s campus damaging the trees and crops in our area,” Porter said.

“I am also a part of the Duquesne Community Garden that is maintained by the Laval House that I help the ecology club keep track of. There are so many examples of topographical things like that in which we want to strive to keep their beauty.”