Ollie Gratzinger | Features Editor

11/09/2017

“Before LeBron James, before Stephen Curry, there was Chuck Cooper.”

Spoken by Chuck Cooper III, President and CEO of the Chuck Cooper Foundation and son of the NBA legend, these words are sure to resonate with any basketball fan or sports history buff here at Duquesne.

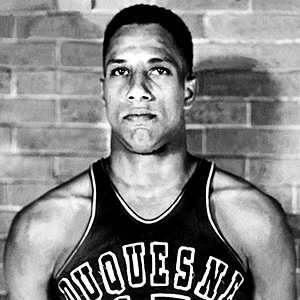

When the Boston Celtics chose Pittsburgh native Charles “Chuck” Cooper as the 14th overall pick in the 1950 NBA Draft, history was made: In that moment, Cooper became the first African American drafted into the NBA.

However, his story doesn’t just start there.

Before he was drafted into the world of professional basketball, he was drafted into the United States Navy during the twilight years of World War II. Before that, even, his aptitude for academics, music and athletics set him apart throughout his education at Westinghouse High School. Later, when life led him to the Bluff, he established himself as an irreplaceable talent with a kind, guiding nature.

On the court, he was incredible, setting the school’s then-record of 990 career points while leading the Dukes twice to the prestigious National Invitational Tournament (NIT), according to the Chuck Cooper Foundation website. Off the court, as his son says, he was an inspiring leader with a “strong commitment to education” and a constant willingness to help others as best he could.

“He was a great man,” said Chuck Cooper III, who heads a nonprofit in his father’s honor. “A family man, adored my mother, adored his four children. He just really enjoyed being around his close friends and family. I was definitely blessed and lucky.”

Cooper III went on to explain how his father’s influence inspired him to help others.

“I ran a youth program back in the early ’90s when Pittsburgh was having a big gang problem,” he said. “What inspired me to do that was that I wanted to give these young men and women who came from broken families an opportunity to experience some of that guidance and mentorship that he provided me.”

Chuck Cooper’s legacy prevails to today not only in his inspiring kindness or his retired No. 15 Duquesne jersey, but also in the prominence of his accomplishments.

“He was afforded a great education and the opportunity to become a leader on and off the court,” Cooper III said. “He was an All-American and the team captain, and both of those are very rare at a predominately white institution back in those days.”

Cooper was a pioneer in athletics, breaking down segregation barriers and making a name for himself in spite of society’s bigotry.

Cooper III described certain times that his father faced injustices while playing basketball in a predominantly white sphere.

“I can’t even imagine — teams going off to have their team dinner and he can’t sit down with the team; he has to get a brown-bag meal through the kitchen door,” said Cooper III. “His [Celtics] Hall of Fame coach, Red Auerbach, is quoted as saying ‘Chuck Cooper had to go through Hell.’ I just really can’t even imagine.”

Where many might have quit or turned back in the face of such discouragement, Chuck Cooper persevered and excelled. For as challenging as it was to be a trailblazer in a time that didn’t welcome diversity, he was able to find a home in his time with the Dukes.

“He always felt very supported by the university, the coaches and the players,” Cooper III explained. “I think that his love for the university was really forged in the late ’40s when the University of Tennessee came [to play] Duquesne. They didn’t want to play if Duquesne allowed my father to participate, so they took a team vote. It came back unanimous, and they sent Tennessee home without a game. So,” he continued, “my father, I think, really developed a lot of respect for his teammates, his coaches and the university.”

Chuck Cooper’s story is one of triumph and gentle greatness. Regardless of ethnicity or athletic involvement, all of Duquesne can proudly boast the shared narrative of his timeless legacy.

Cooper III’s sentiments echoed the actions of his father.

“Education is the key to success,” he said. “Know that there’s nothing you can’t accomplish if you put the work in.”