By Seth Culp-Ressler | Features Editor

Duquesne archivist Thomas White reaches for a shelf, just one of the many that fills the room to the brim with boxes, books, memorabilia and folders. He carefully chooses a slim, square blue carton. Opening it and folding away the tissue paper reveals its unusual contents: it’s Adolf Hitler’s pillowcase.

“It’s kind of become a legend on campus,” White says.

White is Duquesne’s curator of special collections, to which the piece of Hitler’s linens belongs. Stored on the first floor of Gumberg Library, the pillowcase lives in one of two main rooms packed full of the university’s archives and special collections.

Duquesne’s archives have made the news recently in connection with “The Day Hitler Died,” a Smithsonian Channel Special that premiered this past Monday night. The special’s primary resource was a series of filmed interviews conducted by Judge Michael Musmanno, a former Pennsylvania Supreme Court Justice. In the late ‘40s Musmanno spoke with the individuals who were in Hitler’s bunker during his final days in late April of 1945.

The interviews are part of the expansive Musmanno collection, which was donated to the library in 1980. So why has it taken over 65 years for these talks to reach the greater public?

“The Musmanno collection takes up about 1,000 linear feet,” White said. “There’s so much stuff, and the films were unlabeled, sitting in boxes. We knew – at least it was rumored – that the footage was there, but we started with processing the papers and the documents first.”

Beyond just locating the footage, there were also concerns of damaging the decades-old film, as well as the fact that the Musmanno family still holds the copyright. Eventually, in the mid-2000s, a German company got permission to produce a documentary using the films, which it ended up releasing around 2010. But there was still a slight hitch.

“They had a three-year deal where they would have exclusive rights to the footage, but they only showed it in Germany,” White said. “So as soon as that expired Finestripe Productions was interested in making one for everybody else.”

It’s the Scottish-based Finestripe Productions’ version that premiered last Monday.

Interestingly enough, the interviews used to create the documentary merely scratch the surface when it comes to the entirety of the Musmanno collection. White said Musmanno was involved with an astonishing array of historically significant events. He was involved in the famous Sacco and Vanzetti trial in the twenties, the break up of the Coal and Iron police in Pennsylvania in the thirties, an early anti-drunk driving campaign and a raid on the Communist Party headquarters.

“His life is kind of like a capsule history of the first sixty years of the twentieth century, we have lots of interesting material there,” White said.

Musmanno’s collection falls into one of three different areas collected by the archives and special collections – that which deals with World War II and the Cold War. While Musmanno’s collection is the single biggest contributor to that area, there are others that help fill out the assemblage.

One such group of note is the Clarke collection, 400 linear feet of boxes and records that are still being sorted through. James Clarke worked for the State Department and was a spy during World War II. He was also an expert on Eastern Europe, and the collection includes many artifacts from that region, as well as from significant sites such as Pompeii.

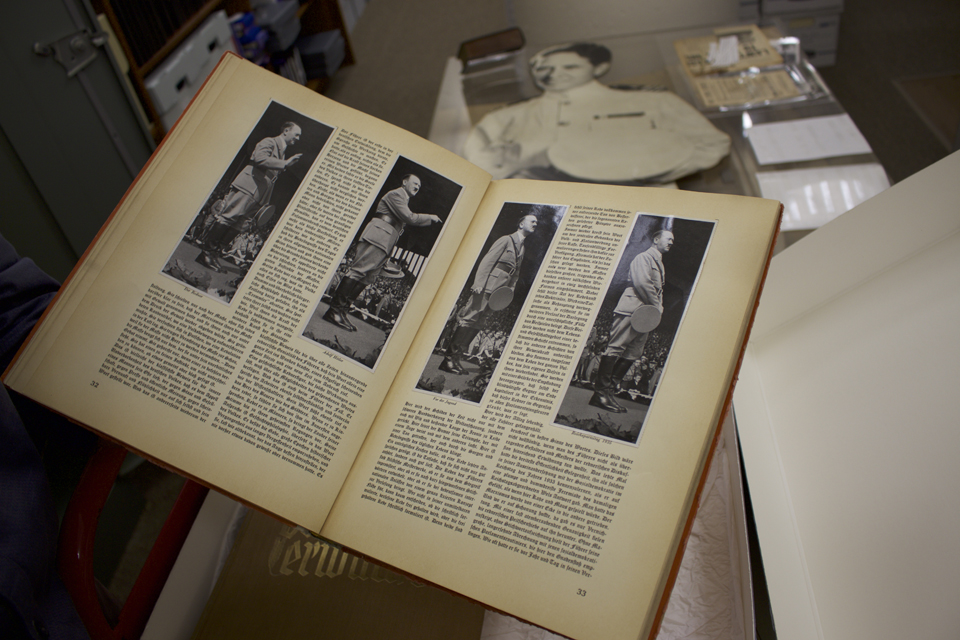

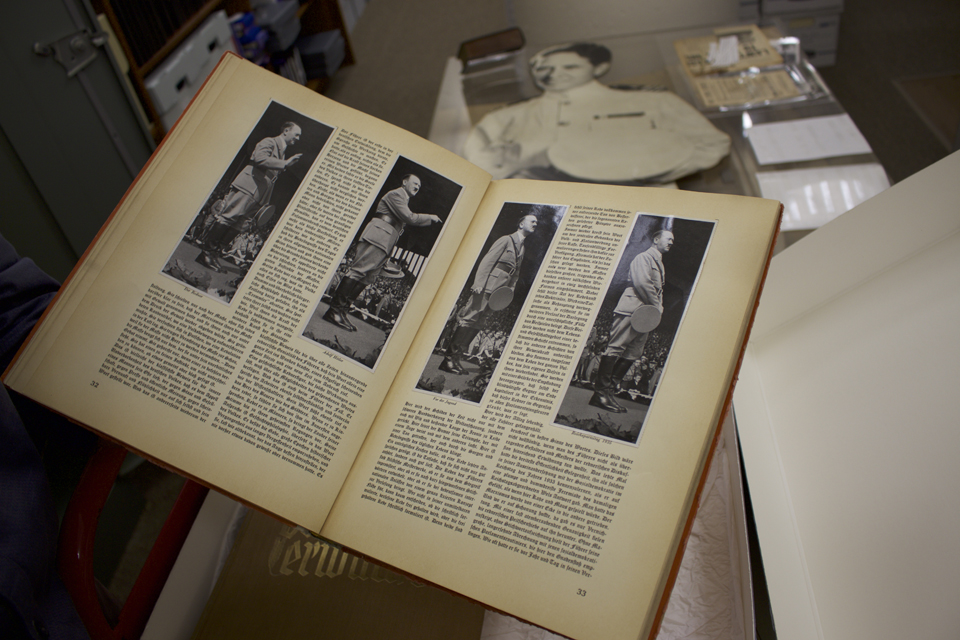

White explained that the special collections also have various other pieces of Nazi-owned relics, aside from Hitler’s pillowcase, of course. Hidden away in boxes is everything from printing plates used to make Hitler’s books to interactive propaganda books.

“[The books are] very similar to ‘Topps’ in the 1970s and ‘80s,” White said. “You’d collect baseball cards, but they’d be stickers, and you’d paste them in a book. This is like the Nazi version of that.”

The other two areas White said the archives collect in are, predictably, Duquesne-specific memorabilia and Catholic-related collections. Within the scope of those two areas can be found everything from a Papal bull dating back to the 1500s to books focusing on Christian-Jewish relations that go as far back as the 1400s.

This, unsurprisingly, is merely scratching the surface of the full collection as it currently stands. There’s always another box to open, and always a new story to uncover. For White, that’s the beauty of it.

“I like working with the actual materials,” he said. “It gives you a better sense of what was going on. It puts you more in touch with the history when you see the actual items and the things that were used.”