By Julian Routh | Editor-In-Chief

In newspapers all over the country on April 26, 1950, a small footnote was buried in the sports section beneath stories of New York Giants baseball, quarterly boxing revenue and the 76th Kentucky Derby.

The footnote read, in most instances, “First Black Player Drafted to NBA,” with a few sentences underneath about a 6-foot-5, 200-pound African American man with agile athleticism being selected by the Boston Celtics in the second round of the professional draft.

That man was Charles “Chuck” Cooper, a Pittsburgh native who had just led the Duquesne men’s basketball team to two National Invitational Tournament bids. His story – on way to officially breaking the NBA’s color barrier – is one of resilience and bravery, sweeping its way through the Bluff in the 1940s.

Cooper was born in 1926 to Daniel and Emma Cooper, a mailman and school teacher, respectively. The youngest of six children, Cooper pursued multiple sports at Westinghouse High School in the footsteps of his oldest brother, Cornell.

On the high school basketball team, Cooper was rarely given the chance to shoot the ball. Instead, he rebounded, played defense and opened up space for other players; a style of play he called “dirty work” and detested, according to the Chuck Cooper Foundation.

But his high school coach, Ralph Zahniser, told him he had a bright future in basketball, so he continued to play. En route to Pittsburgh’s city championship, he averaged 13 points per game as a senior and was chosen as the All-City first team center.

Cooper then followed several other talented young black players to West Virginia State College, where he played a semester before entering the military in the winter of 1944. He completed a tour of duty on the West Coast during the late stages of World War II and then returned home to Pittsburgh, where he enrolled at Duquesne.

In four years as a starter, he amassed a school-record 1,000 points and led the team to a 78-19 record, including two trips to the then-prestigious NIT. He was captain of the squad during the 1949-50 season, the first in which the Dukes were nationally ranked throughout the entire year. He was named a consensus second team All-American.

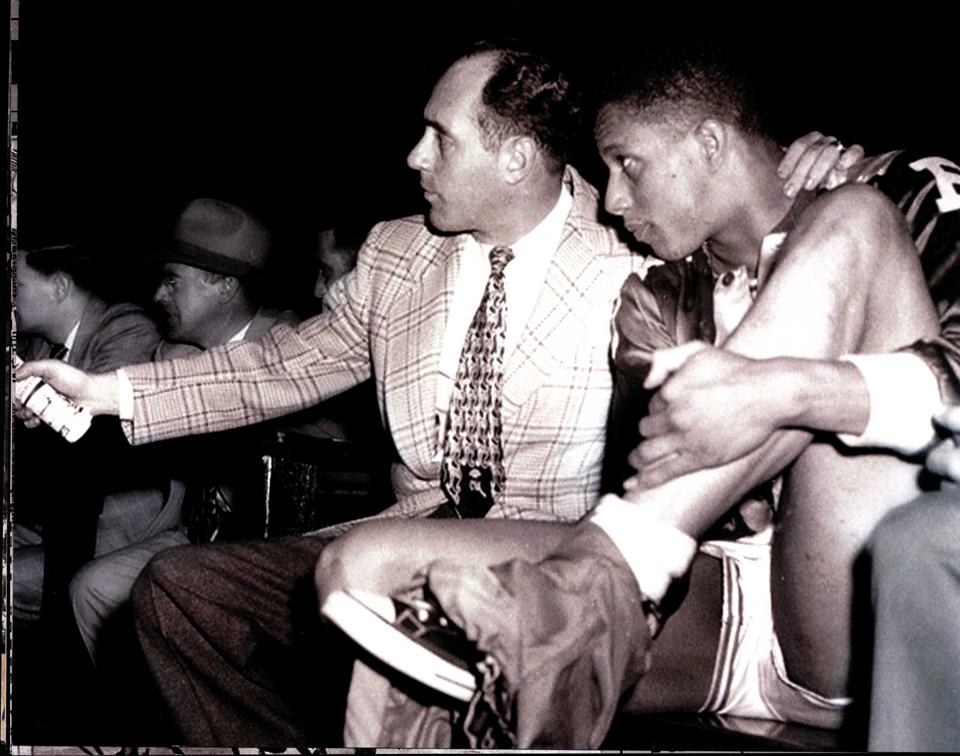

But Cooper’s participation in the game of collegiate basketball angered some opposing teams, most notably the University of Tennessee in 1946. On Dec. 23 of that year, Tennessee coach John Maurer refused to send his team out on the floor in protest of Cooper playing in the game. Duquesne head coach Charles “Chick” Davies insisted on playing Cooper, and the game was cancelled.

In a historically brave announcement to the 1,500 fans on hand, Duquesne athletic committee chairman Sammy Weiss said, “In accordance with the athletic policy of Duquesne University, we do not bar anyone because of race, creed or color. Therefore we cannot jeopardize our principles by agreeing to Tennessee’s demand.”

After graduation, Cooper embarked on a 17-city tour with the all-black Harlem Globetrotters over 18 consecutive nights in 1950. The Globetrotters wanted him on the team into the summer, but Cooper was approached with a different opportunity in April.

With the 12th overall pick of the fourth annual NBA draft, the Celtics selected Cooper amid much scrutiny. When one owner asked Celtics owner Walter Brown why he drafted a black player, Brown famously responded, “I don’t give a damn if he’s striped, plaid or polka dot! Boston takes Chuck Cooper of Duquesne!”

Cooper went on to play six years of professional basketball. He made his debut against the Fort Wayne Pistons on Nov. 1, one day after Earl Lloyd became the first black player in NBA history to take the court in a game. Lloyd was selected in the ninth round of the 1950 draft by the Washington Capitols.

Cooper averaged 9.5 points and 8.5 rebounds in 66 games during his rookie season. He played four years in Boston, one year with the Milwaukee Hawks and one year with the Pistons, which included an appearance in the 1956 NBA Championship.

Cooper died of liver cancer in 1984, one year after Duquesne established the Chuck Cooper Award to honor talented basketball underclassmen.

Duquesne retired Cooper’s No. 15 jersey in 2001, a worthy ode to one of the school’s most immortal players. Though he never admitted it, Cooper was a trailblazer on a path that certainly wasn’t easy.

But if anyone could make it look easy, it was Chuck Cooper.