Luke Henne | Editor-in-Chief

Oct. 20, 2022

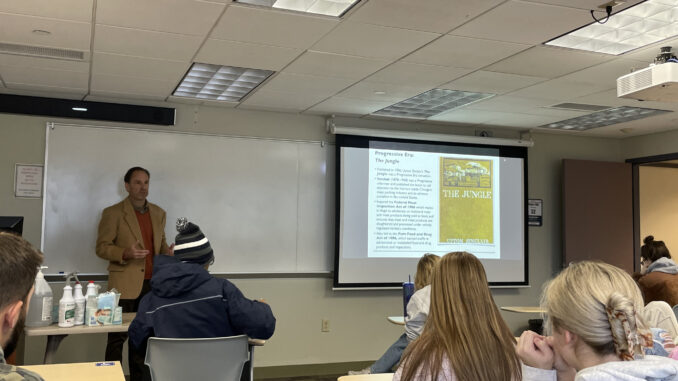

Daniel Holland, an adjunct professor at Duquesne, hopes that his students walk away from his courses with a deeper understanding of meaningful, contemporary issues.

Whether that’s in History of Sport, Early American History or Food, Social Justice and Sustainability, Holland hopes they’ll be able to make connections with the real world.

“It’s not so much about me, quite frankly,” Holland said. “What I’m hoping is that something I said in the process that we’ve put together for the class is something that leaves them with a little bit more of an informed thought process, so that they have an idea of ‘Hey, I’m going to go out and look for the truth’ and ‘I’m going to ask good questions.’”

While Holland focuses in many different areas of history, sport has always been a focal point of his life. He ran track during his time at Carnegie Mellon University. Both then and now, Holland remains an avid runner. He uses the lessons he’s learned in his sport participation to shape how he thinks in a larger context.

“I’m an athlete myself. I’ve been an athlete all my life, and I’ve also asked myself many of the same questions that we ask in class,” Holland said. “When I stand on the starting line of a 10K race, I have this awareness of race, of class, even of gender and so on. I have this filter, even as I’m participating in sport sometimes.”

He also said that sport is something that, naturally, many people can connect with.

“From an academic perspective, sport, more than anything, is one of those things where everyone has an opinion about it, and everyone interacts with it in a different way,” Holland said. “It’s pretty ubiquitous throughout our society. It’s just everywhere. I think it’s a great way to understand society because it both shapes society, and it reflects society.”

By understanding that almost everyone has some relationship to sport – whether they’re an athlete, an employee or just a fan – Holland hopes to engage his students through active discussions that allow them to share their experiences and make connections between those experiences and the bigger-picture issues.

“As far as I’m concerned, just talking at students without an interactive component is one way of teaching, but it may not be the most-effective way,” Holland said. “I think most people learn best when they can interact with the material.

“The [in-class] discussions give people an opportunity to really think through what they’ve learned over the past week … It’s what we call the Socratic method, from Socrates, where you have this give-and-take, where you have an opportunity to really inquire and dig a little deeper into a subject that particular week, other than what you read, or what you watch, or what someone tells you in the front of class.”

Holland’s History of Sport class will be offered in the upcoming spring semester. But it goes beyond the societal issues that sport can provoke. This fall, Holland he’s teaching the aforemtnioned Early American History and Food, Social Justice and Sustainability courses.

He hopes students will apply what they learn in the class to the real-world conversations that come up regularly.

“I want [the students] to make the connection with the contemporary world, especially the Early American History [course],” Holland said. “Here we are, just a couple weeks away from the midterm elections, and people should be asking questions: What does the Constitution guarantee? How did we get to this point in our society? Are there other precedents for what we’re experiencing today? These issues of race, class and gender. Are they new? Or has this been something that has been discussed in previous generations?”

In the latter of the aforementioned courses, Holland explores pertinent issues that may seem simple, but that have a lot of societal impact when considered more carefully.

“I’m encouraging people to ask good questions about what is on their plate for dinner, lunch or breakfast, and what kind of information are they using to make informed decisions when they go shopping, or when they order at a restaurant,” Holland said. “All these things are really designed to raise awareness, more than anything.”

These key questions stem from Holland’s experience in the external world. He feels that working to make connections with communities of color and communities in low-income areas is the best way to bridge the gap and help create a more-cohesive society.

One of Holland’s major projects that emphasized his commitment to improving that relationship was his founding of the Young Preservationists Association of Pittsburgh during his time in graduate school at Carnegie Mellon in the early 2000s, a time in which there “really wasn’t a good youth culture in the city.”

“It seemed like there weren’t a lot of youth-focused organizations, and there was a lot of concern about the loss of young people,” Holland said. “It seemed to me that every problem was an opportunity, and what I wanted to do was create an opportunity for young people, especially to engage with the communities around them, with the history in their communities.

“It was really designed to encourage young people to get more engaged and involved in their communities, especially with the history of their communities, to learn the history of their community and then find ways to save it and preserve it.”

In the academic world, Holland has worked closely with Rob Ruck, a history professor at the University of Pittsburgh. Ruck praised Holland’s ability as an educator and as a citizen, describing him as a “very incredible human being.”

“What Dan has done is, to me, embody the best about an academic, which is that he built social capital,” Ruck said. “He has been intimately involved in Pittsburgh neighborhoods, and understanding and writing and studying those neighborhoods, but also trying to make sure that those neighborhoods have access to the resources they need to develop.”