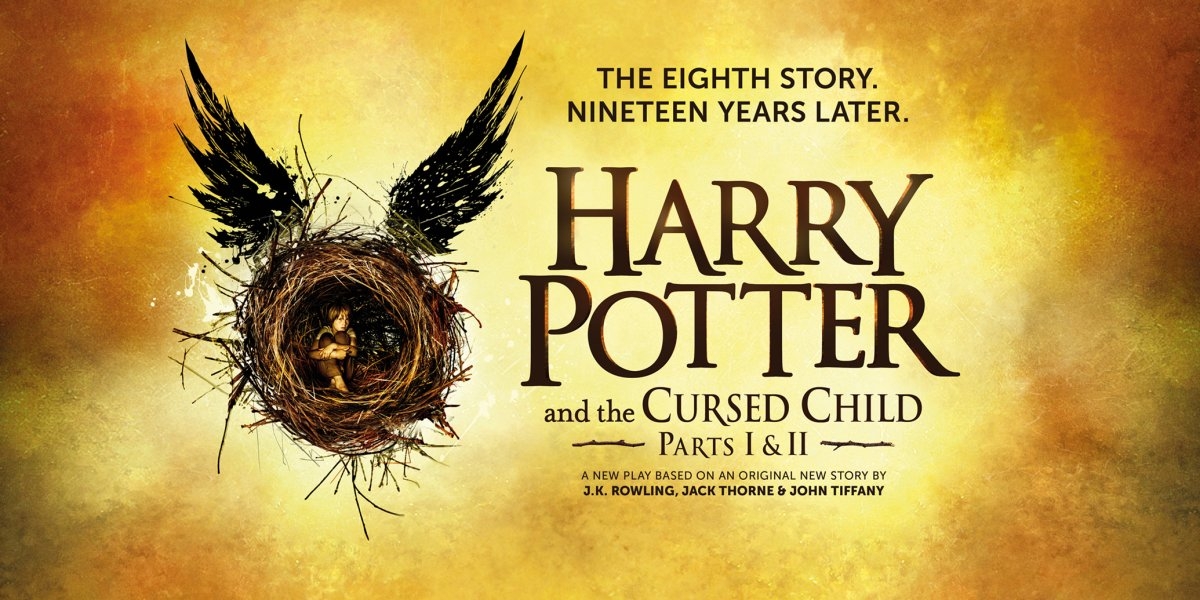

Unlike the novels that proceed it, Harry Potter and the Cursed Child starts with main protagonist Albus Potter’s fourth year, rather than his first.

By Nicole Prieto | The Duquesne Duke

“Harry Potter and the Cursed Child,” the much-anticipated eighth installment of J.K. Rowling’s saga, made its print and digital debut on July 31, just a day after its Grand Opening Gala Performances at the Palace Theatre in London. The newest original story, written by playwright Jack Thorne, gives fans a taste of the world after Harry Potter’s son, Albus Severus Potter, takes his first train ride to Hogwarts.

Unlike the camaraderie, warmth and adventure that defined Harry’s experiences at the magical school, all is not well for the youngest Potter son — who, as a Slytherin, faces loneliness and ridicule for failing to live up to his father’s legacy. With his only friend, demure Scorpius Malfoy, as his light in the dark, Albus forges his own grand adventure when he attempts to right a wrong that has haunted his father for two decades: the murder of the Triwizard Tournament “spare,” Cedric Diggory. The notorious time-turners from “Prisoner of Azkaban” make their return in an adventure with enough alternate universes to sate the imagination of any diehard fanfiction writer.

As with its predecessor novels (perhaps depending on the fan), “Cursed Child” can be read in a day, keeping true to Rowling’s captivating and uniquely magical world. Expect floo powder, magical duels, time travel and a dash of Polyjuice Potion to round out this rendition of the Wizarding World. Those who cannot see the full production in London will not be disappointed by the script-book’s sparse descriptions of scenes and action; the dialogue easily carries the audience from Albus’s disappointing first-year and growing estrangement from Harry, to the climatic final battle.

“The Golden Trio” make full appearances as well. Harry is Head of the Department of Magical Law Enforcement, Ron Weasley runs the family joke shop and Hermione Granger has the unsurprising role of Minister of Magic. A “Harry Potter” installment would not be complete without Draco Malfoy, whose obnoxious attitude has cooled down greatly over the years in place of an overprotective paternal instinct. (And a new ponytail.)

Unfortunately, the play does not make full use of the main characters as much as the audience would hope. At the risk of sounding sacrilegious, Ron does not really need to be in the play at all. His role is to be an affectionate husband and mildly embarrassing uncle, perhaps tempering Hermione’s role as a major world leader. Aside from offering some comic relief, he is not given much to do as he tags along awkwardly in major scenes. If the play could function without Luna Lovegood and Neville Longbottom, surely it could have survived excluding a member of the fabled trio — at least, just this once.

The characterizations are largely appropriate for the 20-year interval from the victory at the Battle of Hogwarts to the start of Albus’s fourth year. Albus Dumbledore’s memory, now stored away as a living portrait in Hogwarts, confronts Harry about his strained role as a father to him. Dumbledore admits to failing to tell Harry how much he cared, and Harry does not withhold his own frustration at Dumbledore’s distant nature during his life. It is a brief, cathartic scene that adds some dimension to Harry’s decision to name his youngest son after a man who was arguably the most capricious of Harry’s stand-in parental figures.

Draco’s treatment as a character is likewise well-handled. While still boasting a sense of superiority and a short temper, Draco is plausibly developed as a mourning widower and concerned father. He recognizes that his child is almost his total opposite as a person, viewing it as a trait warranting Scorpius’s protection. His desperation at keeping his only family close and safe occasionally overshadows Harry’s concern for Albus, but mirrors the same concern his own parents had for him during the war.

That being said, Thorne does jerk around the audience in some scenes for no reason, at times taking violent shortcuts with Rowling’s characters.

After Albus and Scorpius return from their first trip in the past to try to prevent Cedric from winning the tournament, and thus from getting killed by Voldemort, they wind up in an alternate timeline. Fearing Scorpius’s influence on his son, the Harry in this world cruelly tells Albus that he is forbidden from seeing his friend ever again, turning rabid in his insistence to Headmistress Minerva McGonagall that Albus must be watched in the Marauder’s Map at all times. While this is a scene that could at first be written off as a consequence to the boys altering time, it is implied that this is a moment that would have been consistent between the original and new timelines. It is awkward and greatly out-of-character for the adult Harry we have since become acquainted with.

Thorne’s veracity also comes into question when, upon the boys changing time again, it is revealed that all it would take for Cedric Diggory to become a Death Eater would be for him to be publicly humiliated during the Tournament. This is perhaps the play’s strangest twist, considering Cedric’s long regard in the “Harry Potter” fandom as a noble character.

Perhaps the play’s most awkward flaw is its tension with one of its overarching themes: children not needing to be their parents. Follower-type Scorpius is no Draco, and Slytherin, slow-to-broom-flying Albus is no Harry. Both sons feel pressed by the legacies their headstrong parents left behind them, with Scorpius left particularly vulnerable in a world that suspects Voldemort, via time travel, is his actual father. Without spoiling too much, the play has a hard time reconciling whether having a noble versus ignoble parentage truly defines you as a person, something it fails to give a clear answer to.

Overall, “Cursed Child” is a satisfying addition to the “Harry Potter” canon. Though its writing is by no means free from flaw, it succeeds in reintroducing Harry’s story to nostalgic readers and moviegoers alike, giving closure to fans’ curiosity about the war-scarred world Harry and his friends needed to rebuild from as adults.