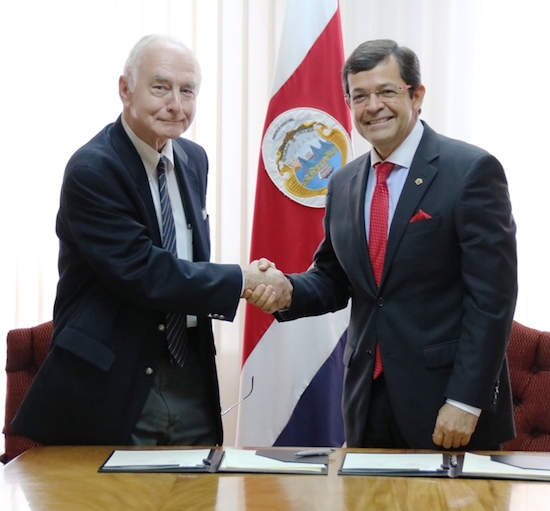

Duquesne law professor Robert Barker shakes hands with Justice Carlos Chinchilla, president of the Costa Rican Supreme Court. They renewed a cooperation agreement.

Duquesne law professor Robert Barker shakes hands with Justice Carlos Chinchilla, president of the Costa Rican Supreme Court. They renewed a cooperation agreement.

Raymond Arke | News Editor

In late June, Duquesne law professor Robert Barker traveled to the land of deep rainforests, pristine beaches and “one of the most stable and respected legal systems in the world,” Costa Rica.

Barker visited the small Central American country to renew a more than 20-year-old academic cooperation agreement between Duquesne’s School of Law and Costa Rica’s Supreme Court. The program includes Duquesne professors traveling to give lectures, Duquesne students doing internships for the Costa Rican Supreme Court and Costa Rican jurists giving presentations at Duquesne.

Barker, a distinguished professor of law emeritus with a long connection to Central America — especially Costa Rica — was essential in laying the groundwork and building up the cooperative program. He first visited Costa Rica as a member of the Peace Corps stationed in Panama in 1968, not long after receiving his undergraduate and law degrees from Duquesne.

“I was a Peace Corps volunteer not in Costa Rica, but in Panama at the time. And we were working to establish a legal services program for the squatter settlements of [Panama City],” he said.

Since Costa Rica had a similar program to what Barker was working on, he made his first trip to the country.

“I persuaded my boss in Panama to send me up to Costa Rica, so I could take a look and perhaps gain some information that would be useful back in Panama,” Barker said.

The trip was successful and Barker returned to Costa Rica in 1984 with a research grant from Duquesne to study its system of judicial review, which lead to more trips and the creation of the agreement in 1995.

“From 1984 on, I visited CR pretty frequently and wrote articles which eventually got put together into a book,” Barker said. “Duquesne Law School cooperation with Costa Rica began in 1995 when a justice of the Costa Rican Supreme Court, Justice Luis Fernando Solano, suggested to me that a program of cooperation be established between the Costa Rican Supreme Court and Duquesne.”

Solano thought it would be good for Duquesne professors to teach at the Supreme Court’s judicial school, where Costa Rican jurists are trained, and for student exchanges to happen. Since 1995, Barker said that the cooperation has yielded many results.

“A number of Costa Rican judges and Supreme Court justices have visited Duquesne University … and participated in a couple of seminars on constitutionalism in the Western Hemisphere. Several Duquesne professors over the years have gone to Costa Rica and given talks at the judicial school, various universities and the Supreme Court,” he said.

Along with the Supreme Court, Barker also mentioned that Duquesne has agreements set up with one of Costa Rica’s top law schools and is working with the relatively young Catholic University of Costa Rica on their law school.

“We have been asked to help advise/participate in the creation of a law school at the Catholic University of Costa Rica. They’re interested in some cooperation with Duquesne,” Barker said. “There’s no specific program yet, but it looks like we will have some sort of working relationship somewhere in the near future.”

The President of Costa Rica even visited Duquesne in the fall of 2014 to receive an honorary degree from the law school.

Along with his many visits, Barker has said at least two Duquesne students have been able to make the trip for summer work.

“Two DU law students in the past … visited Costa Rica for summer internships with the Supreme Court of Costa Rica and they profited a great deal from the experience. They enjoyed it very much,” Barker said.

Eduardo Benatuil, a current Duquesne law student, was one of those interns. He called it a “wonderful and unique education experience.” Costa Rica’s Supreme Court is divided into four chambers, each of which deal with a certain topic. Benatuil was placed in the Constitutional Chamber.

“As an intern, the first few days of my internship were spent learning about the Constitutional Chamber’s procedure, and familiarizing myself with how constitutional questions were brought to the court, reviewed by clerks and deliberated upon by Magistrates,” he said.

As the internship progressed, he was primarily tasked with working on health care issues.

“My main focus in my internship was to work on constitutional questions and petitions related to health care … I was given the opportunity to draft legal opinions and Supreme Court orders, in Spanish … [and I] prepared constitutional protective orders for health, restraining orders and injunctions to ensure the prevention of health care abuses of patients and petitioners,” Benatuil explained.

Benatuil explained that interning in a foreign court helped him in numerous ways.

“The experience helped me learn about the unique attributes and functions of the judicial system of Costa Rica, as well as the different elements of the nation’s health care system … The internship experience also gave me a unique opportunity to work and interact with judges, Magistrates, law clerks and government officials, and also allowed me to draft protective orders and legal opinions that were used/published in actual cases involving constitutional questions of health care,” he said.

Ken Gormley, President of Duquesne and former dean of the law school, also praised the Costa Rican connection.

“This has been an extraordinary experience for our students, who have had the chance to work directly for Justices of the Supreme Court and utilize their knowledge of both American and international law to assist the Court,” he said.

He hopes that the links between a school and a foreign country’s top judicial body continue in the future.

“Costa Rica, a nation with a strong Catholic tradition and a stable democratic form of government, has been an ideal partner for Duquesne’s students and faculty, which has benefited the entire institution,” Gormley said, “We are looking forward to a rich a fruitful relationship between the Costa Rica Supreme Court and Duquesne for many years to come.”

Barker believes that opportunities like this to cross international boundaries are crucial in helping Duquesne law students to be prepared for a modern world.

“There used to be a time when lawyers had no foreign legal problems, maybe a hundred years ago, but now with so much travel and so many business transactions that cross national boundaries, it’s more and more likely that even the most local lawyer is going to have, from time to time, international legal problems or questions,” he said.