Filmed in Butler County, Pennsylvania, Night of the Living Dead had an initial budget of $114,000 and grossed $30 million internationally. The Wall Street Journal reported that it was the top-grossing film in Europe in 1969.

By Josiah Martin | Staff Writer

02/22/2018

Very rarely does a work of art both create and perfect a genre at the same time. Night of the Living Dead, which celebrates its 50th anniversary later this year, arguably did just that.

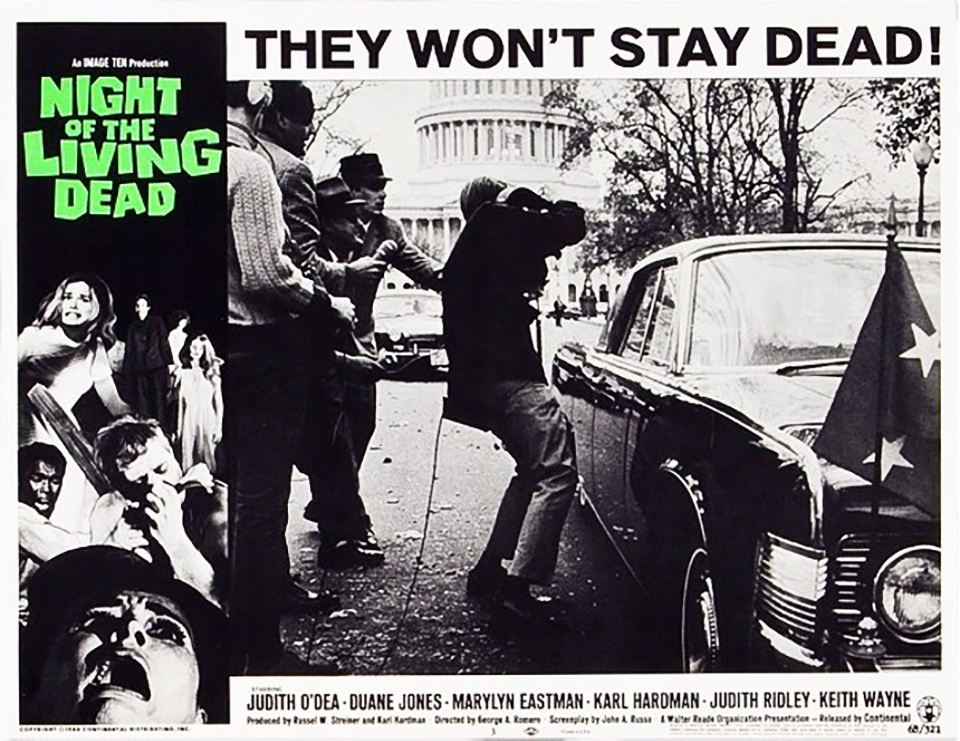

Directed by George A. Romero and written by Romero and John Russo, Night of the Living Dead may not be the first film that comes to mind when you think “horror masterpiece.” In fact, it has all the trappings of a ’60s sci-fi B-movie: It was made on an extremely small budget, filmed in the middle of nowhere (Butler County, Pennsylvania), stars no-name actors, features over-the-top gore and was filmed in black and white despite being released in the late ’60s. However, Night of the Living Dead is saved from becoming midnight-movie camp by the pure talent of the people involved.

The gore in the film isn’t shocking in the traditional sense. Aside from one early exception, the audience isn’t hit with sudden, disgusting shots. Rather, the gore is even darker than that: It’s slow, detailed and deeply repulsive. Shots that carry intense emotional weight or are particularly visually disturbing are paired with pulsating, low, electronic sounds or a screeching hiss that make the visuals all the more bothersome and hard to watch — but greatly compelling.

The film, like most great zombie-themed works, focuses on the people instead of the monsters. It is soaked in more Cold-War era distrust and paranoia than blood. This choice is a testament to Romero’s writing.

For example, I recommend taking note of how few characters actually die at the hands of the reanimated corpses encroaching on our heroes’ secluded farmhouse. Most perish instead as a result of self-sacrifice, anger, confusion or revenge. The film is about the people, not the supernatural, and the fact that Romero nailed this distinction as early as ’68 makes the film impressive, compelling and deeply watchable.

The characters themselves act believably like someone in their situation would. Barbra, one of the first characters we meet, is catatonic for a majority of the film. Harry Cooper, who has stowed himself and his family away in the basement, is selfish and determined to protect only his own interests. Tom is young, naïve and just wants to make sure his girlfriend Judy is safe.

Above all is our main character, Ben, portrayed masterfully by Duane Jones. In an era where the issue of representation in film is only just beginning to get the attention it deserves, seeing a black protagonist that fits no preconceived stereotypes and whose race isn’t intended to be a major focal point of the film is surprising. This is especially so for a film made in rural Western Pennsylvania in the ’60s.

Ben is the level-headed member of the group — except in a select few situations where he violently reacts out of frustration with the other characters and the situation at hand. Again, this is a testament to the realism of the film. If the dead were rising from their graves and devouring the living, it’s safe to say a fair majority of the population would get a bit angry from time to time.

A few justifiable criticisms arise when talking about the characters. The female roles serve no real purpose for the majority of the film. While the film is tragic and nobody really gets a true heroic moment, Romero and Russo’s writing leaves all women in the house simply waiting for something to happen around them.

Additionally, some of the acting of the smaller parts is certainly sub-par, made only worse by a few odd edits during scenes of extended dialogue. These issues aren’t distracting from the bulk of the film, which remains brilliant both visually and narratively.

The film notably features Bill Cardille, legendary Pittsburgh broadcaster, playing himself as a reporter for WIIC (now WPXI). Though the film has universal appeal, so much about it is uniquely Pittsburgh. Keen-eyed natives will also notice familiar place names such as Butler and Greensburg on the television during news broadcasts. Barbra and Johnny drive up the region’s trademark uneven terrain in the opening shots of the film. There is both a news helicopter and a button on the radio for recently-defunct AM radio station KQV.

As Pittsburgh becomes more of a film-industry-friendly city, it should remain proud that Night of the Living Dead is one of its more prominent cinematic exports. It is required viewing for all horror fans, or cinephiles in general, and thanks to a copyright filing error, is available free and legally on nearly any website that hosts video.

The film still holds up and its social critiques still ring true after half a century. To paraphrase one of the film’s taglines, Night of the Living Dead “won’t stay dead,” and will likely live on in film history for another 50 years.