Hallie Lauer | News Editor

Almost every middle school science fair has the project where a student takes two plants and tries to see how different types of music affect its growth. But picture this instead: rather than playing music for the plants, the vegetation itself creates the music.

Paul Miller, an assistant professor of musicianship at Duquesne, along with Brian Riordan from the University of Pittsburgh, have been studying ways in which the electrical charges from plants can be turned into music.

“To be clear, the plant is not making music,” Miller said. “We’re making the music, and the plants provide the raw materials.”

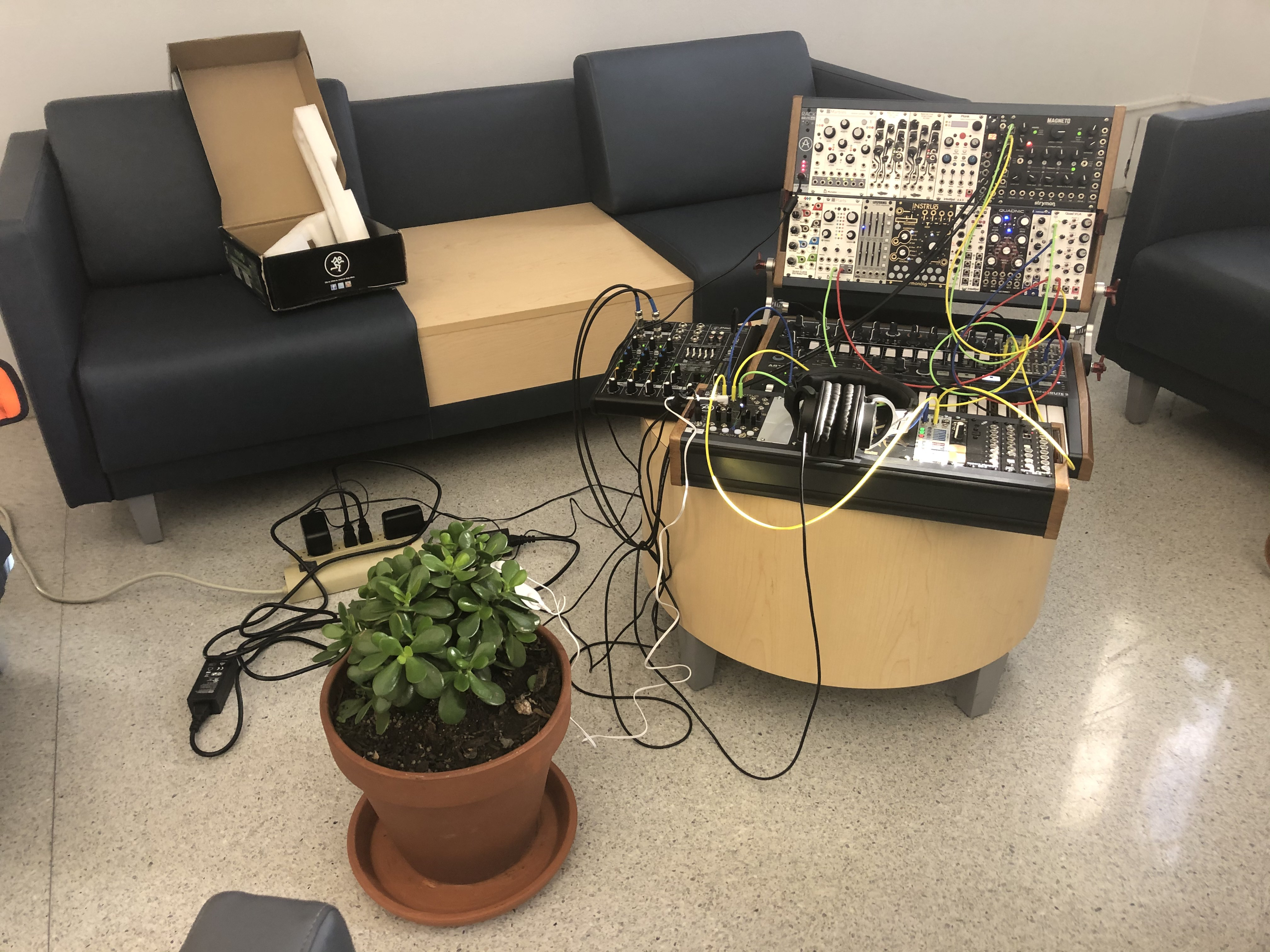

Miller uses a synthesizer with a specially designed interface to transform the small electrical signals from the plants, into a level that can be used in music.

Synthesizers work by manipulating electrical voltages to produce a steady pitch that can then be turned into music. Miller helped to build the synthesizer at Duquesne about a year and a half ago. When he found this interface, he decided that it would be an interesting project to work with vegetation.

“The plants in some way are controlling the synthesizer,” Miller said.

Miller explained that the majority of the time, signals used in the synthesizer are periodic, like a sine-wave or random, like white noise. He said that the best sounds come from signals between periodic and random.

“The plant provides really good semi-random signals,” he said.

Miller and Riordan have studied two common house plants, a jade plant and a cornstalk plant. They attach sensors, similar to the ones used in a lie detector test, to the plants leaves. This allows the synthesizer to collect the electrical charges and transform them into pitches that can then be translated into music.

Between the two they have studied, both give off different electric signals. However, those signals are not unlike the electrical signals that the human body also gives off.

The jade plant tends to give a more stable signal while the cornstalk plant has a more active range of signals. But it also depends on the settings of the synthesizer if those changes can be picked up.

“I don’t know that it’s helped me to make really good music yet. I’m still working on it,” Miller said. “I can, hopefully, in the next year or two make really great music.”

The goal of this research is to find a new way for composers and musicians to collaborate, as well as connecting classical music studies with new electronic music.

“This is reaching across a very wide gap. We talk about gender or wage gaps, but we other plants all the time,” Miller said. “When we reach across the plant-animal divide we are reminded of our place in the cosmos. It gives us a sense of time and a chance to collaborate with a partner that may outlive me.”

The plants signal not only to themselves, but other plants as well. When listening to the synth, the listener can hear a change in the electrical charges as something comes near the plant or when the plant is touched.

While the plants cannot think or feel, they can perceive and react to changes in their environment.

“No one realized plants did this until Charles Darwin studied Venus Fly Traps,” Miller said. It is the electrical signals that plants send that cause the Venus Fly Trap to close when an insect lands on it.

The next step for Miller and Riordan is to subject the plant to environmental changes, like different soil or burning a leaf on the plant to see what kind of voltage is produced.

“[Our] next stage is to find a cell biologist,” Miller said. “And then we want to publish.”

Miller and Riordan took their findings to the 2019 Society for Music Theorist annual conference in Columbus.