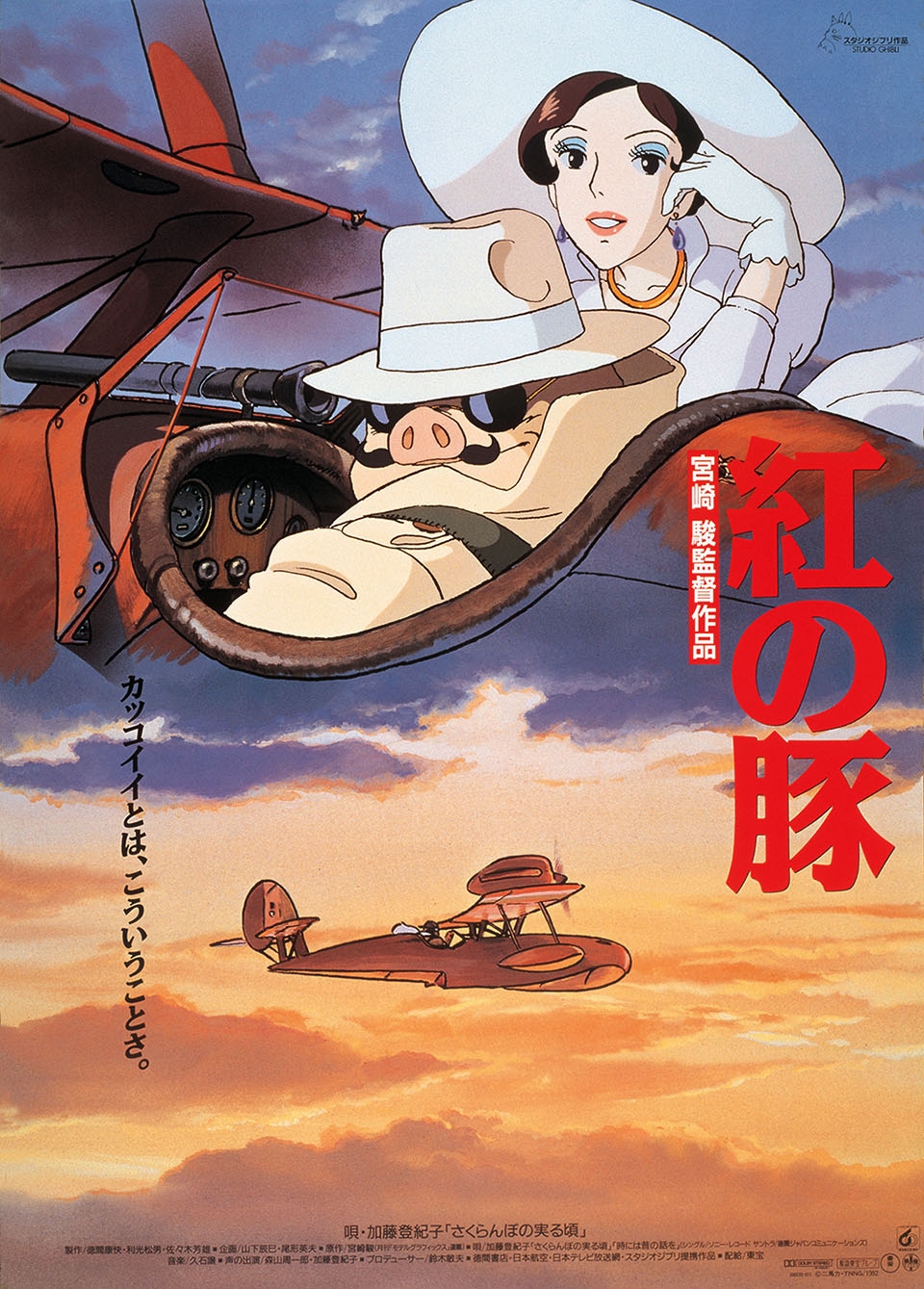

‘Porco Rosso’ is the fourth film that Miyazaki has written and directed with Studio Ghibli, following ‘Kiki’s Delivery Service’.

Nicole Prieto | Staff Writer

10/26/17

From aerial acrobatics to daring dogfights with seaplane pirates, Hayao Miyazaki’s Porco Rosso is the epitome of family-friendly adventure with a dash of noir sensibilities. This gem about a circa 1930s ex-World War I pilot mysteriously cursed to bear the face of a pig is a timeless classic about love, honor and survivor’s guilt.

Porco Rosso is just your average bounty hunter trying to live from one hard-earned moment of peace to the next. Between shootouts with comically incompetent air pirates and evening dinners at his friend Gina’s Hotel Adriano, the celebrity Ace of the Adriatic’s ideal day is lounging beachside at his secret hideout. But all that changes when American pilot Donald Curtis shows up with a promise for the pirate gangs frustrated with Porco’s success: He will keep the pig out of the skies — for good. With Curtis and the pirates at his neck, and the Italian air force at his heels, the “Crimson Pig” must now defend his friends, his coveted plane — and his peace and quiet.

As always, Miyazaki’s storytelling is without equal, and Porco Rosso is no exception among contemporaneous hits like My Neighbor Totoro or Kiki’s Delivery Service. The beauty is how much the director-writer revels in revealing key narrative details through a sense of absence. The negative space surrounding lone planes that dot open skies impresses upon the audience the wonder and freedom that Porco enjoys whenever he flies. The movie takes advantage of quiet moments where all that can be heard is the hum of a plane engine and the gentle soundtrack scored by Joe Hisaishi.

Characters’ sincerest emotions are often revealed through their eyes, making Porco’s insistence on wearing dark sunglasses almost unnerving. We are forced to understand him through what he refuses to say or overreact to, from his feelings for the sharp-tongued Gina to how humbled Porco is when his mechanic, Piccolo, employs female relatives to rebuild Porco’s plane. Notably, through his silence, we also learn volumes about the immeasurable weight he carries from the Great War. Porco may take on the trappings of a mysterious noir anti-hero, but he is far more than the womanizing lone wolf (or pig) he projects.

The director’s love for airplanes is on meticulous display without overwhelming the audience with technical details. Fio Piccolo is the young granddaughter of Porco’s Italian mechanic who is prone to spouting off jargon about plane design and engineering principles. Her enthusiasm grounds the audience in the realistic elements of this almost folkloric story, while also reassuring the somewhat sexist Porco that the 17-year-old is up to the daunting task of redesigning his damaged plane.

As a writer, Miyazaki balances the drama of Porco’s complex inner world with tasteful humor designed to appeal to as wide an audience as possible. During a dogfight, Curtis calls out Porco for being “chicken” for refusing to engage in battle, to which Porco responds, “Chicken? Pig? What’s the difference?” Later on, Porco criticizes the excessively-gregarious Curtis — who has since proposed marriage to two women he just met — for not “know[ing] anything about girls.” But Miyazaki and the film’s English translation are hardly content with taking advantage of Porco’s penchant for being a smart aleck. This beautiful Ghibli film indulges in a healthy amount of well-animated slapstick — from an uptight Porco getting visibly wind-tossed by a test run of his new engine, to his major dogfight with Curtis devolving into an impromptu boxing match (complete with referee).

As a visual work of art, the film’s only faults are stiff camera pans in a handful of scenes. But that hardly detracts from Studio Ghibli’s significant attention to atmosphere in highlighting the complex world that Porco belongs to. The film’s positive overtones are supported by vast swathes of beautiful landscapes, sparkling seas, open skies and almost vacation-worthy locales.

Hardly any of that changes when Porco or Gina reminisce about the difficult times they have lived through. Porco’s guilt over the death of his best friend is illustrated with a palette of crystal white and blue. Gina reveals the news about her third husband’s confirmed death in Asia within the warmly lit restaurant of her hotel. Miyazaki’s tale is as much about hope and recovery as it is about the cruel realities of war. We never lose grasp of the movie’s sense of adventure. But through its somber moments punctuating idyllic scenes, we are gently reminded that heroism is not always equipped to resolve life’s inexplicable hardships.

Appropriately, the film leaves the audience without definitive answers to some of its most persistent questions. Will Porco become human again? Will he and Gina fall in love? Will he defeat Curtis once and for all?

The answers are, perhaps bafflingly, yes and no. This is not the product of frustrating plot holes but the genius of Miyazaki’s careful direction and resistance for clear-cut answers. Porco Rosso is perhaps a more subdued entry in the Studio Ghibli library, but it is no less worthy in quality among Miyazaki’s classics.