Colleen Hammond | editor-in-chief

Jan. 27, 2022

Aged black and white photographs faded across the screen as a pair of violins sung a haunting, mournful melody. A shopkeeper. A town doctor. A local hairdresser. A mother of young children. An aging father with a son away abroad. Almost eight decades after one of the darkest chapters of human history, members of the Pittsburgh Jewish and Duquesne communities gathered to honor the often forgotten lives taken in the Holocaust.

In commemoration of Holocaust Rememberance Day, a memorial holiday designated by the United Nations in 2005, Gumberg Library and the Holocaust Center of Pittsburgh hosted a virtual, interfaith event on the evening of Jan. 26.

“Tonight’s commemoration is an opportunity to remember those who were killed during the Holocaust,” said Sara Baron, Duquesne librarian.

While this secular memorial day attempts to pay respect to the 6 million Jewish people who were murdered, it has become a day to focus on the forgotten voices often lost to the past.

Through the work of the event’s panelists like Lauren Apter Bairnsfather, director of the Holocaust Center of Pittsburgh, the memory of victims of this grotesque genocide are preserved and passed on to future generations.

In her continuing efforts to educate the public on the enduring effects of the Holocaust, Apter Bairnsfather said programs like this are “shedding light on histories we don’t always pay enough attention to.”

Apter Bairnsfather kicked off the night with a slew of introductions followed by the dispelling of a core myth about Holocaust Rememberance Day. Since 2005, this day has marked the liberation of the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp in 1945 by the Russian Red Army.

“Sometimes as our knowledge of history fades, we think the United States was there at the liberation of Auschwitz,” Apter Bairnsfather said.

She also spoke about the underlying importance of Holocaust education in a world that has become increasingly, violently anti-Semetic. Her comments were echoed by Duquesne Hillel President Shai Maaravi.

Maaravi first came to the United States from Israel to attend school at Duquesne. While initially unafraid of life in the U.S., he said things changed rather quickly as he recognized the rise of anti-Semetic language and attacks happening across the country. He said he soon realized how “privileged” his life in Israel was.

“Here in America, life is very different,” Maaravi said. “Until I moved to the United States, I never worried about my life as a Jew.”

Pittsburgh, as several of the panelists noted, is no stranger to the rise in anti-Semitism.

On Oct. 27, 2018, 11 people were killed while attending Shabbat morning services at the Tree of Life Synagogue in Squirrel Hill. Six other congregants were injured.

With the deep wounds of anti-Semitism still healing, Rabbi Hazzan Jeffrey Myers of the Tree of Life Synagogue led the group in a pair of prayers for the dead, one of which asked that “those who have perished be eternally protected by God.”

Joining him in prayer was the Rev. Bill Christy, Duquesne University chaplain. Christy quoted the prayers of Pope Francis on this day in 2020 fully condemning anti-Semitism and spoke of the need for the Church to stand against hate by remembering the terrors of the past.

“Memory…Memory is a must,” Christy said.

In response to this call to remember the past, the event also featured keynote speaker David Rosenberg. Rosenberg, a local scholar and archivist, has been telling the unknown stories of the Holocaust for nearly a decade.

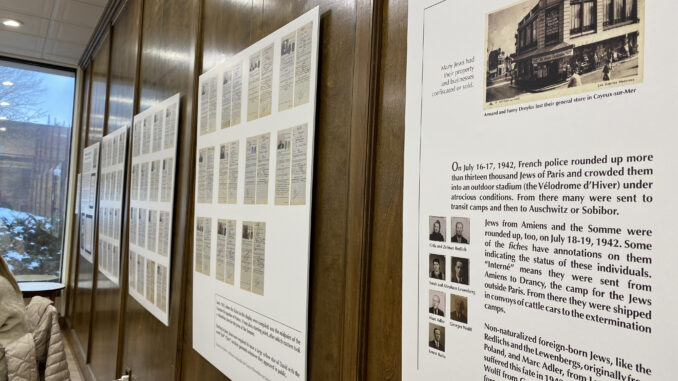

“Sensing a vacuum of knowledge,” he compiled an extensive archive of the stories of the citizens of Amiens, France, throughout World War II which have been curated into an exhibit called “Who is a Jew? Amiens, France 1940-1945.” The exhibit includes several first-hand accounts of life at the time and will be on display on the fourth floor of Gumberg Library until Feb. 4.

Hidden in the most ordinary letters and correspondence, Rosenberg brings back to life the daily struggles of a Jewish community in northern France during Nazi occupation.

One such placard in the exhibit tells the story of Armand Dreyfus, a general store owner in Cayeux-sur-Mer in 1942. In his letter, he asked government officials to stay the eviction order placed against them for the Jewish heritage. He argued that he and his wife should be allowed to stay in the lodgings adjacent to their business, although it was being “aryanized.”

“In explaining my situation I am hopeful that you can intercede in order to annul this measure, which seems to me exceedingly harsh,” Dreyfus said in his March 1942 letter.

Not long after, Dreyfus and his wife, Franny, were arrested and deported to the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp. Neither were known to have survived.

It is stories like these that Rosenberg said he sought “to drive the history into recognition and awareness.”

Learming about these events, however uncomfortable, Rosenberg said, keep the memory of the Holocaust alive and combat the looming threats of ignorance and hatred. In preserving the legacy of the millions of victims, Rosenberg, Apter Bairnsfather, Baron, Christy and Myers hope to do their part to prevent atrocities like this in the future.

“To commit to the pledge never again, we must first never forget,” Maaravi said.