Zach Petroff | Opinions Editor

March 23, 2023

Kirk Bloodsworth spent eight years, 10 months and 19 days incarcerated, including two years on death row, for a crime he never committed.

After five witnesses testified that they saw Bloodsworth on the scene, he was convicted in 1985 in Baltimore of a 1984 rape and first-degree murder of a 9-year-old girl at the age of 24.

Bloodsworth was the first man to be freed from death row in the United States on the basis of DNA evidence.

“If you sat down and made this out to be a movie, people would think it’s a little too unbelievable,” said associate professor of law, John Rago. “Whatever could have gone wrong, went wrong.”

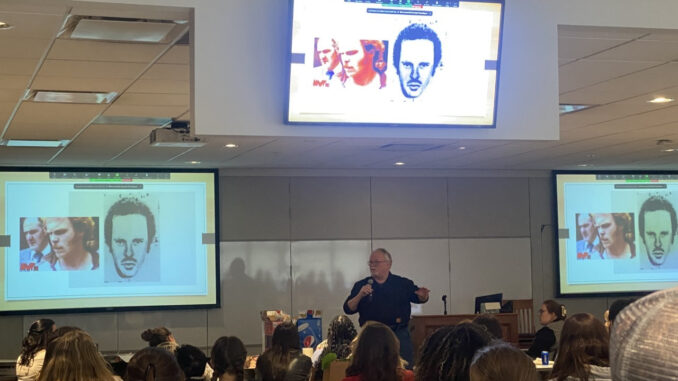

On Wednesday, the Duquesne Student Bar Association hosted Bloodsworth along with Rago as part of a panel called, “Wrongful convictions, conviction integrity and accompanying issues in Allegheny County.”

“I think it’s something that everybody should care about because it affects everybody,” said Student Bar Association vice president, Chole Clifford. “Anybody can be arrested or falsely convicted. I think it’s important to see how this happens and to bring awareness to it so that it can be an issue that more and more people are made aware of.”

Bloodsworth was released from prison and fully exonerated in 1993 and has spent the past 30 years fighting to abolish the death penalty and addressing wrongful convictions. He was the executive director of Witness Innocents, a national organization that gives voices to wrongfully convicted from death row.

“What I admire about Kirk,” Rago said, “he didn’t waste this experience. If it was me, I’d probably go sit in a room and just be depressed for the rest of my life. Angry for the rest of my life. He took his time and did so much good for 30 years when the rest of us would have just taken a seat. I admire him for that.”

The repealing of the death penalty in Maryland, Delaware, Washington State, New Hampshire and Connecticut are a direct result of his activism.

“It took me 20 years to end it in the state of Maryland,” Bloodsworth said. “But no innocent person will be executed there.”

According to the National Registry of Exonerations, the rate of wrongful convictions in the U.S. is estimated to be somewhere between 2% and 10%. With a prison population of about 2.3 million, there could be anywhere between 46,000 to 230,000 innocent people incarcerated.

“I had two trials, 24 jurors, the entire police department from Baltimore County, Maryland, two judges, two prosecutors and every single one of them, including the state of Maryland, were dead wrong about it,” Bloodsworth said. “That’s what wrongful convictions equate to.”

Bloodsworth has also spent his life after death row telling his story, and even after three decades it is evident that the scars from that experience have not healed.

“Well you can imagine what it’s like living in a prison accused of killing a child,” Bloodsworth said. “But if I didn’t do anything wrong, you’re not going to chastise me over it. I stood up to it every day of life, and I didn’t always win out but I bought out more than I lost.”

Bloodsworth’s retelling of his story is filled with harrowing accounts. His prosecution for his alleged murder of a 9-year-old girl, with a lack of physical evidence, only relied on witness testimony.

“Witness identification is one of the leading causes of wrongful conviction in the United States,” Bloodsworth said.

The cheers that erupted when his guilty verdict was read still ring in his ears, and his heart still breaks for the deceased child.

In addition, while he was in prison, Bloodsworth’s mother died.

“She could do the New York Times crossword puzzle in an ink pen,” Bloodsworth said. “She could do them in ink and get it right.”

While he was in prison, Bloodsworth passed the time working in the library, where he picked up reading.

“I read everything from gestalt psychology to Stephen King,” Bloodsworth said.

He also read “The Blooding,” a non-fiction book written by Joseph Wambaugh about how DNA was used to solve a brutal murder. The book gave Bloodsworth the idea to push for DNA to overturn his conviction.

“Here’s the magic in my view,” Rago said. “Here’s a high school graduate that reads a book and says to himself, ‘If DNA can find somebody, maybe it can help to tell them I didn’t do this.’”

Almost immediately after being released from prison, Bloodsworth went to work sharing his story on talk shows and universities.

Rago, who heard Bloodsworth speak about 25 years ago, became motivated to make a change.

“When I came back from listening to Kirk, I thought, ‘What are we going to do in Pennsylvania?’” Rago said. He started reviewing cases and found discrepancies happening in Pennsylvania. There were multiple accounts of eye witness failure, use of jailhouse informants and false confessions.

Rago was able to catch the attention of the Pennsylvania senator for the judiciary committee and started to work on reforms to minimize the risk of error recording custodial interrogations and better evidence preservation practices.

“We’re trying things in Pennsylvania to minimize the risk that [Bloodsworth] suffered,” Rago said. “But none of that starts without him coming to Duquesne University School of Law 25 or so years ago.”