By: Joel Frehn | The Duquesne Duke

Haunting.

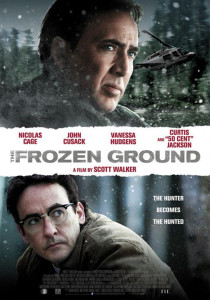

When describing the crime-thriller The Frozen Ground, the one word descriptor, haunting, is the perfect adjective to be applied to the film featuring Nicholas Cage, which is based on true events.

Set in Alaska in 1983, the film follows detective Jack Holcombe (Cage), who is tracking down serial killer, Robert Hansen (played by John Cusack). This scenario — which is prevalent in films in the genre such as Dirty Harry-could not be more relevant with the sentencing of Whitey Bulger still on the public’s mind.

In terms of bringing the film’s interpretations of the real life players to life, The Frozen Ground is a dream casting. After a string of commercial failures, Nicholas Cage has returned to reclaim his position as one of cinema’s A-List performers. It was easy to dismiss him after the botched and misogynistic remake of The Wicker Man (which spawned several internet memes that did not help his reputation) and the crude Ghost Rider films. But, The Frozen Ground serves as a reminder to audiences that this is the same man who won an Academy Award for his performance Leaving Las Vegas.

Cage’s performance, however, is complemented with John Cusack. Cusack delivers an unnerving performance, which contrasts against his most recent foray into the genre, as the fictional crime solving Edgar Allan Poe in The Raven. Each of the men steals their respective scenes, which keeps the viewer on edge.

The film lingers with the audience after the viewing in several ways. In terms of the narrative, Halcombe is driven to apprehend the killer because of his self inflicted guilt. This harbored emotion stemmed from the death of his sister, who is the same age as the victims of Cusack’s character, and the reduced sentence of the intoxicated driver who hit her. In addition to the ghost, the film paints a bleak portrait of the Alaskan frontier; namely, it depicts it as a force that reduces man to his most primal state, connecting to an idea popularized in the literature of Jack London. The sequences in Anchorage focus on the underbelly of it: the bars, adult venues and havens for those involved with prostitution and narcotics. It is in the uninterrupted frontier that we see the missing behavior: murder.

Director Scott Walker reinforces this with the helicopter wide and tracking shots of the frontier, a technique used by Stanley Kubrick in The Shining, when he was making a similar argument about the Colorado wilderness and its connection to the Donner Party. Unlike The Shining, which used classical music and the terrific electronic score by Wendy Carlos and Rachel Elkind to amplify the mood, Frozen Ground does not have a large, or distinguishing soundtrack: the chase scenes are marked with a suite that is not memorable, but serves its purpose. This achievement of the baseline requirements is present in other components of the film, as well.

With these exceptions in the artistry noted, the flaws of the film are components of what make it work. If one has watched “Law & Order” and other procedurals before, there is nothing groundbreaking in this area, and sadly, The Frozen Ground stands in the shadow of 7even, since it does not attempt anything too bold. The only polarizing aspect of the film was its casting of 50 Cent as a pimp. His performance was adequate and the casting decision opens up the age old dialogue on whether musicians should go into films. If anything, the adequacy of the mechanics of the film and performances are refreshing.

In preceding columns, I argued for Hollywood to try to experiment more; however, after having sat through some failed experiments — ones that tried challenging the spectacle, instead of conventions — I have retracted the claim. I was pleased with The Frozen Ground since it tried to be a good film, instead of a great one.